There was a nasty tummy bug raging though the school. Our teacher addressed the dwindling class. “It’s very important,” he said, “to wash your hands after going to the toilet. This is the only way we can stop this spreading.”

Anna Kenna

I thought about this for a moment then put up my hand. “But sir, how can we wash our hands? There’s no soap in the bathrooms.”

The teacher beamed at my clear indignation and encouraged me to write a Letter to the Editor of the school newspaper. I was eight-years-old.

The Awapuni Chronicle wasn’t a flash affair with its black crayon masthead and handwritten stories pasted onto its rippled pages. But my letter was published; I was listened to and very soon we had soap. It was my first lesson in the power of the press and possibly why I later became a journalist.

It’s a career that has served me well and cemented my belief in the power of words to highlight injustice, expose dark deeds and amplify the voices of the weak and disaffected. In my lifetime I’ve seen good journalism topple governments, expose war crimes, unmask institutional child abuse, crusade for social justice and overturn wrongful convictions. The pre-eminent watchdogs of their day - Peter Arnett, David Frost, and Alistair Cooke - were great role models who inspired a generation of young journalists.

But also in my lifetime I have seen journalism, as a distinct craft, morph into an entirely different beast, ‘The Media’. This omnipresent, multi-headed chameleon has traded any sense of the ‘greater good’ for a ratings-driven deluge delivered to an increasingly less discerning public.

My interest is with young people. How is all this landing with them? How can they distinguish true journalism, the objective, diligent pursuit of truth that informs and exposes, from the alphabet soup that flows daily through their multiple devices? Is it important that they do?

British-Iranian journalist Christiane Amanpour says “I strongly believe that journalism is one of the most noble professions, because without an informed world, and without an informed society, we are weak, we are weak.”

There are credible news organisations still championing and modelling good journalism. And role models, women like Amanpour amongst them, who should inspire young people, like the giants of their time, inspired me. It’s just that they are harder to spot in the media snowstorm.

As Lorraine Branham, Dean of the S.I Newhouse School of Public communications at Syracuse University recently wrote in the Huffington Post, “the terms journalism and ‘the media’ have become interchangeable and that’s part of the problem, because media includes everyone- the pollsters, the pundits, the spin doctors. They are not journalists but they help create the avalanche of information in which true journalism often gets lost.”

In the US, applications to journalism schools hit an all time high in 1974 after the Watergate affair. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s role in exposing one of the biggest political scandals in modern history elevated the standing of journalism and clearly spawned a crop of idealistic young reporters.

Today, references to ‘the media’ are often negative and contemptuous and we hover near the bottom in league tables of trusted professions. Then there’s the Trump card, an influential politician who calls journalists ‘dishonest’ and ‘bad’ people, manufactures his own fake news and uses social media to insult, bait and discredit others.

To the veterans among us this is barely worth a shrug of the shoulders. We know attacking the press is the hallmark of someone with the most to lose from scrutiny. As John Pilger put it “Secretive power loathes journalists who do their job: who push back screens, peer behind façades, lift rocks. Opprobrium from on high is their badge of honour.” But is this daily devaluing of journalism doing real damage?

As a children’s author, I get to meet a lot of young people and they give me hope. Many are intensely concerned about global events and are actively engaged in their communities and schools in projects that place a value on altruism. But how many of them see journalism as a future career and is the profession doing enough to attract them?

As a journalism educator, Lorraine Branham is calling for journalism schools to differentiate the true craft of journalism from ‘the media’, revitalise the role of the watchdog journalist and teach students to pursue the truth, wherever it takes them. I believe we should be embedding these notions much earlier, at around nine or ten when many kids begin to develop a social conscience and interest in the world around them. It’s great, at least in the UK, to see First News, a weekly newspaper aimed at 7 to 14-year-olds that aims to get kids talking about the news in an easy-to-understand and non-threatening way.

As journalism threatens to be subsumed by the media fog, maybe it’s time for the profession to recalibrate and re-establish its founding principles. To educate a generation, that may be unaware, about the constitutional role of a free press and its importance to democracy.

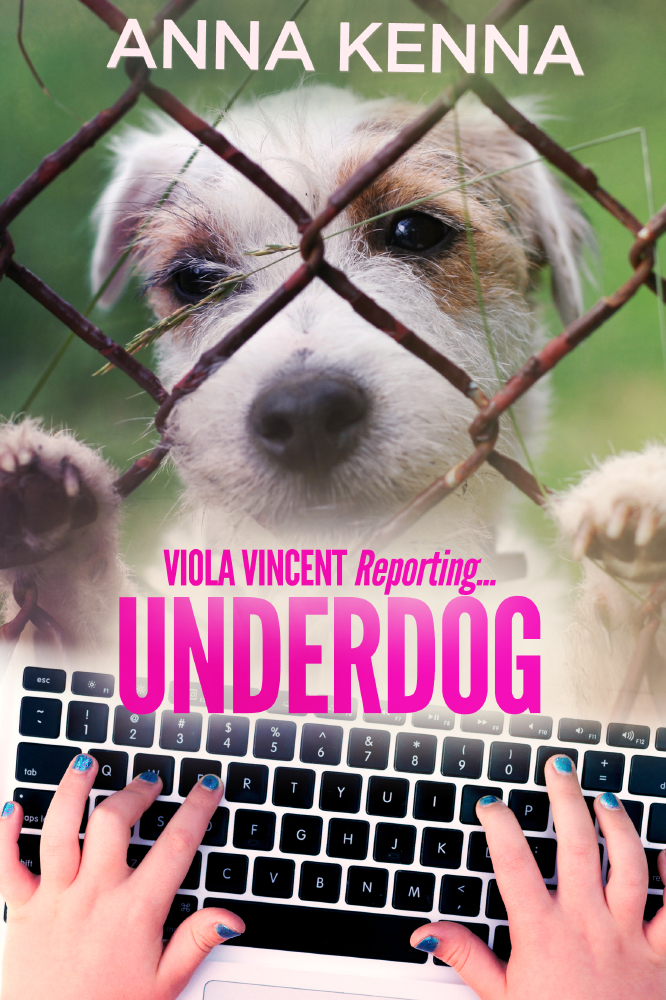

Anna Kenna is an investigative journalist and author of the ‘Viola Vincent Reporting’ series, books for 10 to 13 year-olds, which feature Caitlin Nove, a budding young reporter with a social conscience. www.annakenna.com