Julie Monahan

A few years ago when I had taken early retirement from my career as a social worker, I applied to St Edmunds College at Cambridge University to study for a degree in English. As part of the application, I was required to write a piece about my background. I wrote a page or two detailing my childhood in Dublin and how I had left school at aged fourteen and later gaining a handful of O and A levels at evening classes and progressed to achieving a degree in sociology. I could not afford the fees so I did not take up the offer, but something the chair of the interviewing panel said stuck in my mind. He said I had very descriptive powers and coming from such an underprivileged background I should consider writing an autobiography.

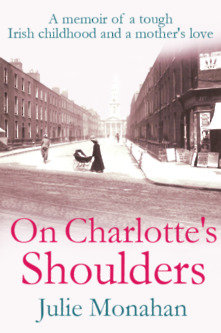

On Charlotte’s Shoulders is an account of my deprived childhood within a large family and the struggles of my mother to rear her ten children, three of whom were mentally and physically handicapped. It is written from the child’s perspective – mine, beginning with my earliest memories from the age of three and ending when I leave Dublin at the age of twenty.

What part of the book did you find the hardest to write?

The book in some respects wrote itself and flowed easily. The hardest part to write was the relationship between my parents, which was always stormy, one riven with discontent and blazing rows. I hesitated to some extent in recording this but I felt it was central to the overall narrative. In fact, I have had to tone it down as it was at times too painful to recall the reality of their troubled relationship, resulting from my father’s fecklessness and inability to put his family’s needs before his own addiction to alcohol. Drink was always his first priority and our family’s poverty was to some extent the result of his addiction and the fraught relationship between him and my mother. Towards the end of the book they reached some form of accommodation when he became too ill to work and spent his last years – mainly sober years – at home with my mother. In a way I felt I was betraying family secrets and this particularly applies to the account of my three sisters’ disabilities. It was driven into us as children,that we must never speak of my sisters to anyone outside the family, such was the shame my mother felt about giving birth to three very damaged children. Towards the end of the book, I give an explanation for the cause of their health problems that explains to a large extent my mother’s antipathy towards my father; her near loathing of him drove her to have an excessive attitude towards him. My decision to write about them led feelings of guilt on my part in breaking this pledge. I would never have resorted to exposing such a dire family secret during my parents’ lifetime. I think however that the memoir needed to be written with total honesty as this was such a huge issue for our family.

What prompted you to write about your early years in Dublin?

Some years ago I enrolled at a class in autobiographical writing at City Lit, in London. These pieces were greeted with many positive comments and I received lots of encouragement from the tutor and class mates who felt strongly that I should try for publication. Also I have always felt that memoirs were written from a male perspective, often from the pens of middle-class writers. (Exception is Angela’s Ashes and one or two others.) This led me to wonder if there might be a market for a memoir written from a female working-class perspective. Like McCourt I wanted my book to finish where I leave Dublin and become part of the Irish diaspora. I also wanted to show the power of the Catholic Church in Ireland then and the control it had over issues like education and family life. I wanted to show the paucity, the narrow and blunted lives where opportunity to develop skills and talents was not available, lives where the business of everyday survival was paramount.

The book has been praised for being a page turner, so how have you developed this addictive quality to your writing?

I have never seen myself as a ‘writer’ and it comes as a great compliment to learn my book is seen as a ‘page turner.’ I write what I know and never have difficulty in putting words down when it comes to genuine experiences. I am not a literary person in the sense that I try to achieve certain effects. Basically, it comes naturally to me. Having said that, there were times I gave up on the whole project believing it to be worthless. It was only through constant encouragement from others – and in particular my husband – that I kept on writing.

How difficult was it to write about a tough childhood through humour?

In actual fact, I originally set out wanting to portray myself as a survivor: how I managed to escape and become educated and find a new life in the UK. But as I wrote, the voice of my mother took over demanding to be heard. It was impossible to ignore her and in the end the book was more about my mother than anyone else. I hope it paints a sympathetic picture of her and indeed of my father as an older man.

The humour flowed naturally as I recalled events and experiences. I did not want it to be seen as a ‘misery memoir’ so I allowed humour to come through. Yet I did not set out to make the reader laugh. The humorous parts of the memoir arose spontaneously as my mother’s voice took over, demanding to be heard in all her faults and frailties. She was as she is depicted: a strong woman with a tongue that could lash but with a sense of humour and a way of speaking that was often very funny. In truth, when my parents were at ease with each other, there was a lot of humour in their interaction. It was impossible to write about family life without including the more humorous elements.

Many of your readers are begging for more, so what is next for you?

The fact that readers seem to want more from me is one of the biggest compliments I have been paid. I never dreamt that my modest efforts could have this effect on my readers. I have started work on a second volume which details my life after leaving Dublin. It will not contain a lot of detail about my parents and I therefore am finding it harder to make it as interesting as On Charlotte’s Shoulders. However the second volume shows some drastic changes in my fortunes as I become educated and start on a professional career as a social worker and become appointed as magistrate. In many ways, though I ask myself, ‘who wants to read about an ’ordinary’ person?’ I struggle with this feeling and lack of confidence in my ability to interest the reader further.

What is your writing process?

I am not sufficiently disciplined to spend a set number of hours at set times each day writing. I do not have a set pattern or routine. I sit at my computer as the mood takes me. It depends how I feel, but once I start writing and the ideas begin to flow as I recall events and characters I stick with it, all the time editing as I go. I then delete or embellish whole chunks until I am satisfied with my efforts. It always surprises me how situations and people who were an important part of my life come alive once I allow my mind to freely wander over my past.

Which writers do you most admire?

I tend to prefer writers of Irish extraction – Anne Enright, Colm Toibin, Sebastian Barry, Roddy Doyle to name a few. I particularly admire the work of Alice Munro and my favourite book is James Joyce’s Dubliners. As a native of north Dublin, this book has a strong resonance for me. I am currently taking a novel writing course and my reading list includes: Patrick Hamilton, Scott Fitzgerald, Molly Keane, Muriel Spark and Jennifer Egan. For light relief I read detective fiction; I am constantly drawn to the novels of Scott Thurow despite their complexity. I think he has a rare insight into the human mind.