In the earliest stages of writing LET ME DIE IN HIS FOOTSTEPS, I spent a good deal of time researching and documenting the traditions and folklore of Kentucky. My findings included customs from across the state. More than any other type of research, studying these traditions gave me insight into the people of Kentucky and those things they most valued and cared to preserve. From these superstitions and tales about family, love, marriage and death, my characters emerged. I understood what they dreamed of and what they feared. The research also made me consider the traditions that have been passed down through my own family, or more importantly, the traditions I have let die.

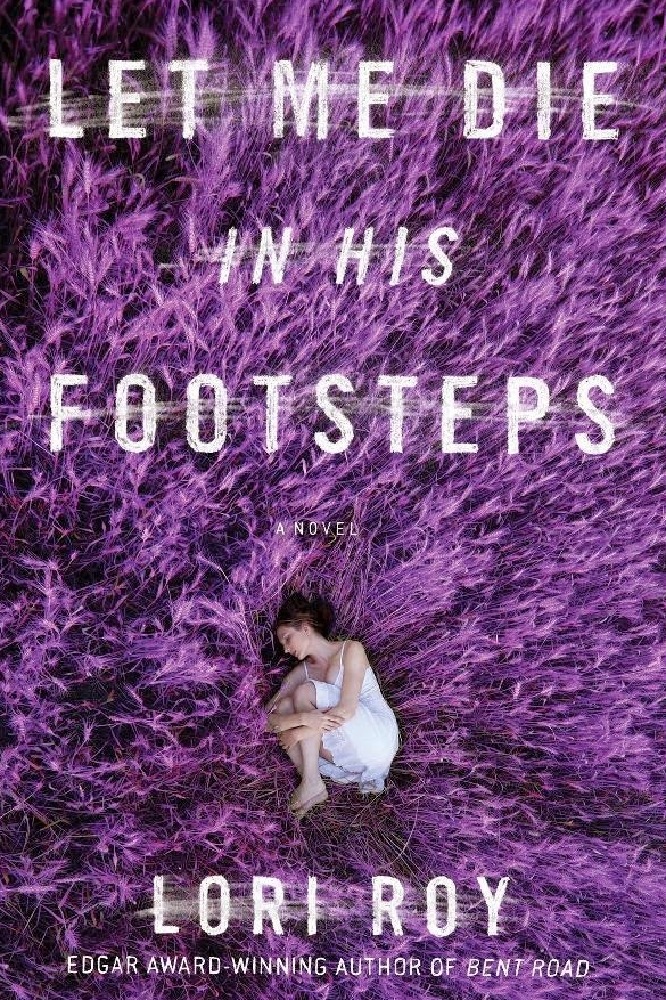

Let Me Die in His Footsteps

I was ten years old when my family last celebrated May Day. Even back then, only a handful of our friends still carried on the fading tradition. Every year, as the last of sunlight disappeared on May 1st and the sky turned from blue to purple to black, the neighborhood kids and I would run from house to house. At each brightly light porch, we would leave a white basket we had lined with green, plastic grass leftover from Easter and stuffed with wrapped candy. Muffling our voices and stifling our laughter, we'd knock three times and run, sometimes stumbling over one another, because if we were discovered, we would have to give a kiss to the one who caught us. At each house I visited, I knocked and ran as fast as I could, hoping not to get caught but enjoying the thrill that I might. That's what I most remember-the thrill. The thrill of getting caught, the thrill of spending time with friends and family and the thrill that spring had finally arrived after a long, cold Kansas winter. The grass was turning green. The flowers were blooming and beginning to smell sweet. School would soon let out for the summer. May Day was a time to celebrate this rebirth. My mother had done the same with her family, as had her mother before her, and on and on.

While May Day managed to survive in the seventies when neighbors still knew one another and children played in front yards, it has not survived in an era when baskets of candy left anonymously on a porch would end up in the garbage. No one talks about May Day anymore when May 1st rolls around. As I sat down to think and write about the role of folklore and tradition in literature, I asked my own daughter what May Day meant to her. "It's a distress call," she said. "It's what pilots say if their plane is going down." Folklore and traditions connect us with our past, connect great granddaughters to the grandmothers they never knew, but only if someone cares enough to pass them along. I had failed because one of my family's traditions had died.

Come next May Day, I'll buy a few small, white baskets. I'll have my daughter stuff them with plastic grass and wrapped candy, and I'll ask that she deliver them to a few of her friends. It won't be quite the same. She won't know the tightness in her stomach as she creeps up to a lighted porch, and we live in Florida now so the arrival of spring isn't quite as sweet. The grass is always green here and the flowers bloom year-round, but I've told her the story of what May Day once meant in our family and I'll tell my son too when he comes home from college. My hope is that that they'll pass it on to their children and then someday, on to their grandchildren.