By Martin Cohen, author of Bounty of a Stolen Empire

Bounty of a Stolen Empire

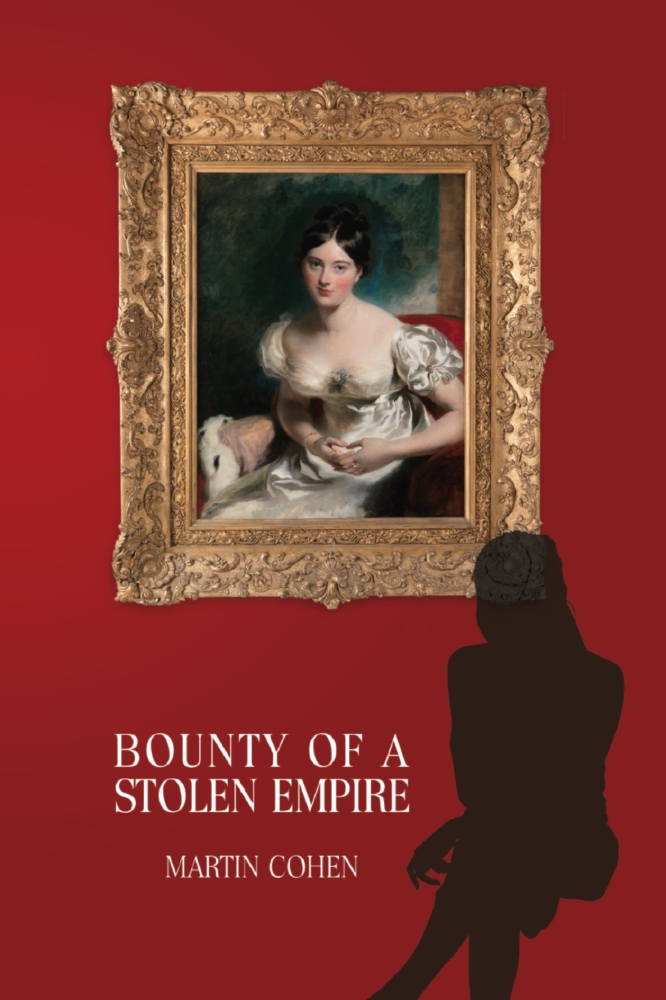

Art lovers among you will be familiar with the flashy (some might say fleshy) portrait of the Countess of Blessington by Sir Thomas Lawrence. It’s the one that welcomes you to the Wallace Collection with an optimistic hint that there could be other provocative works in the magnificent gallery.

But did you know that the Countess (1789 – 1849) was once the highest paid writer in the land? In her best years she probably earned in today’s money as much as J K Rowling’s and Hilary Mantel put together. This doesn’t mean that she was a particularly good writer. Nothing she wrote ever got a rave review.

No, she was a particularly good businesswoman. She was particularly good at eliciting outrageous advances, fees and royalties. And she was particularly good at exploiting her ample femininity and numerous friendships with the good and great - every Victorian literary figure you’ve ever heard of, and most of the prime ministers too - and playing off one publisher against another.

So how did this arresting beauty and preeminent socialite, brought up in an Irish backwater, acquire the skills that made her simultaneously famous and infamous? In three words – the hard way - the incredibly hard way. A shrewd precocious teenager, driven to support her ill-fated family, Margaret Power, as she was born, learned her trade in the hostile corn markets of Tipperary, outwitting the boorish dealers who fathered the cowboys of the Wild West.

Her own father, Edmond Power, is a minor squire and social climber with an ultra-inflated ego, whose every endeavour turns to dust. Among his more spectacular failures is the sale in matrimony of his fourteen-year-old pregnant daughter to the insane Captain Farmer, who in an uncontrolled fit of violence almost murders his wife of twelve weeks. Margaret’s unborn child is dead and she is barren for life.

This horrendous experience and her dramatic rescue, far from traumatising the multi-talented child, makes her determined to succeed as no other woman of her time. And she does - for a while.

Twelve turbulent years later, the re-christened Marguerite, now an accomplished English lady, is again sold in matrimony. Her once lover and feigned husband, Thomas Jenkins, extracts £10,000 (say five million today) from a highly-eccentric bisexual, gullible multimillionaire. Charles, Earl of Blessington refuses to marry until his purchased trophy’s missing legal husband is found - brutally murdered.

Scandal and misadventure follow the fabulously rich Blessingtons for seven years as they roam Europe, idling from one grand palace to the next in a ménage á trois with the fascinating spendthrift young dandy, Comte D’Orsay – and other curious bedfellows.

The Earl, heir to half of Dublin and vast estates in County Tyrone, dies prematurely. He leaves a punitive will of disastrous complexity. Marguerite’s legacy is a miserly two-thousand pound (a million or so today) annuity. The poor woman must live by her wits – in unmitigated luxury.

Through a traumatic twenty-year widowhood, she writes novels, poetry, cod philosophy, travelogues, editorials and the thousands of letters still to be found in libraries around the world – and socialises with men of influence, mostly much younger than herself.

You might have never heard of the Countess of Blessington, but you certainly would have if she only had told her whole unvarnished story in her lifetime.

Bounty of a Stolen Empire permits her a second chance to do so. In my fictionalised historical romance, the Countess returns to earth in all the glory of Lawrence’s masterpiece, in the guise of a modern middle-class woman. She scolds her similarly reincarnated past biographers for their errors, omissions and misconceptions. As they appear, she tells the most significant individuals in her life what she really thought of them, and remonstrates with an odd assortment of modern visitors as they comment on her portrait. And she pulls no punches.

The American author, A P Terhune once bracketed Lady Blessington with such immortals as Cleopatra, Helen of Troy and Lady Hamilton among the Superwomen he selected from world history.

I am convinced he made a good choice, which is why Bounty of a Stolen Empire presents the Countess’s adventures as a vivacious cocktail of violence and murder, vengeance, and blackmail, war and peace, poetry and pathos, sex and perversion, love and romance, all spiced by her sardonic wit, sarcasm and satire to guarantee a lingering aftertaste.

Though, I cannot commend her out-of-print works with sincerity, I can say with assurance that Marguerite, Countess of Blessington was a feminine icon who deserves a more prominent place in history.

Lawrence’s portrait celebrates her beauty, but she was and remains a compelling if flawed artwork in herself.

Bounty of a Stolen Empire is now out priced £11.99 in paperback and £11.39 in Kindle edition. Visit Amazon UK.