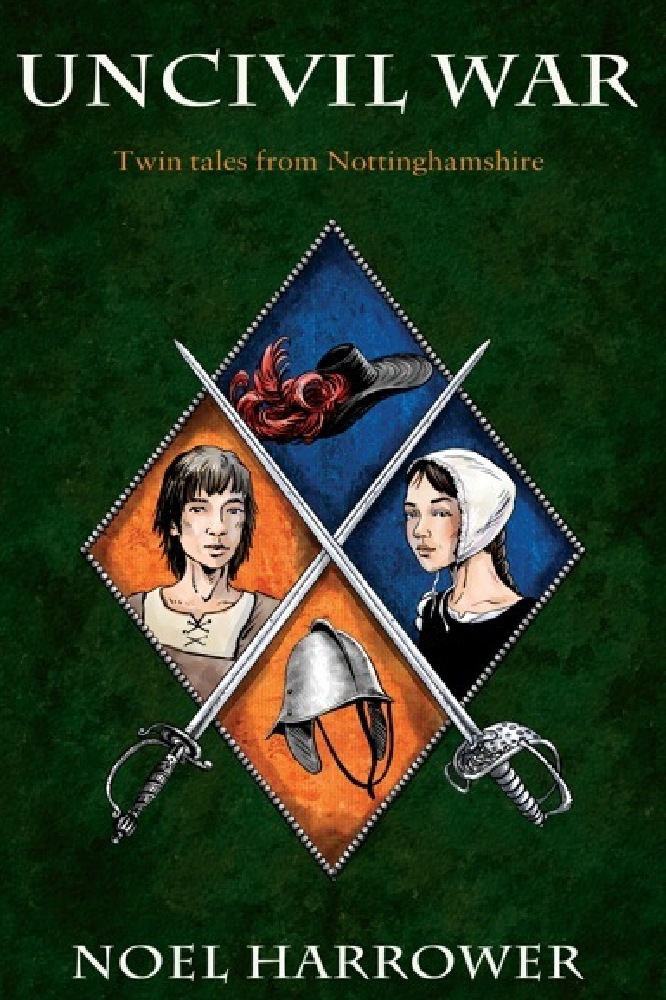

Uncivil War

UNCIVIL WAR is a book about conflict and resolution. The principal characters are a young working class boy, Tom Marriott, a stable lad and his sister, Meg, maidservant in a royalist household. When John Hutchinson, Tom's master, sides with Parliament, Tom finds himself at odds with Meg, and their teenage rivalry catches fire in the storm that suddenly surrounds them. They have little or no choice about which side they are on. Another boy who does make a decision of his own, Jed Martin, soon regrets wearing royalist colours. He signed up for the King's shilling, excited by the clothes and the weapons he is given, but changes sides when he has the opportunity, and is bullied and runs away, only later to be tortured by the round-head officers. The brutality of civil war is universal. Tom and Meg develop more mature minds as the story advances. Their trials and tribulations help them to develop judgement which serves them well.

Please tell us about your research process for the book.

I have always been interested in history, doing a degree in this at Manchester University, and later taking an interest in the local histories of places I have lived in: Warwickshire, Nottinghamshire and my retirement county of Devon.

When I arrived in Nottingham, my office was within a stone's throw of a plaque on a wall announcing that this was the spot where King Charles 1st raised his standard in 1642. I went to the library and read Wood's "History of the Civil War in Nottinghamshire." This led me to join an Adult Education Course on the subject run by Nottingham University. My attention was caught by the fact that Lucy Hutchinson had written her own account of the war in which her husband had held the post of Governor of Nottingham Castle. I bought a copy of her book from a second hand dealer, and discovered that she was a strong minded woman, judgemental but brave. I was hooked on the subject.

How much have your studies in history helped you to write this book?

Having studied history certainly helped. I knew something of the times, and where to go to find out more - the County Record Office and the Local Studies Department of the library, for a start. There were some relevant articles in the Thoroton Society journals, and the idea of writing a novel about these events fascinated me. I was more interested in the ordinary townsfolk than famous people like the King and Cromwell. I bought an old map of the town, and walked the streets to find evidence of where the town walls and gates had once been and the weekday market held. I went over to Newark and spent a day in their library. In the museum were some steel helmets of the period and siege coins dating back to the time when the town was encircled by the invading Scots army. In the parish church, I found an inscription about Hercules Clay, a mayor of the town who had a miraculous dream which saved his family when his home was struck by cannon fire. A timbered old house had a sign on it to say that this was where Queen Henrietta Maria had stayed.

Ideas were buzzing in my head as the story lines began to take shape.

Why do I think few people have written books about this before?

It surprised me that few people had written novels about the Civil War in Nottinghamshire. Numerous books have, of course, been written about the English Civil War over the years, both historical and fictional. There is the standard work published many years ago, "The Civil War in Nottinghamshire" by Alfred C. Wood, which was the first one I read and, of course, there is the contemporary account, Lucy Hutchinson's Memoirs of her husband, John Hutchinson, Governor of Nottingham Castle. These books led me to read about the events in Nottingham and Newark in particular. The same incidents are touched on in many other books on Nottingham, such as those by Thoroton and Bailey and the Nottinghamshire County History, and many short pamphlets have been produced in recent years. What surprised me was that I could only find one novel on the subject, "A Cavalier Stronghold - a romance of Belvoir" by Mrs Chaworth Musters. This book, which is a highly romanticised and far fetched Victorian love story, focuses mainly on Leicestershire, only glancing at Nottinghamshire occasionally. Most of the well known novels about the Civil War, such as Marriott's "Children of the New Forest", or Quiller-Couch's "Splendid Spur", were written many years ago and are set far away from Nottinghamshire, which is where the war officially began with King Charles's raising of the Standard and where it almost finished with the arrest of the King at Newark by the Scots Army. A more recent story, "By the Sword Divided", was set mainly in Northamptonshire. The events in Nottinghamshire form a compact separate story, basically a contest between two rival towns, and my attention was caught by several references to children trapped in the conflict. Here, I felt, was a tale worth the telling that no one had picked up on, despite its national significance, and several wonderful incidents, such as the quarrels between the father and the brothers in the Pierrepont family, the Hutchinson memoirs, the Hercules Clay interlude, and the drummer boy who alerted Newark at the time of the first of their three sieges.

How important is it for writers to bring history to the present?

Yesterday's happenings provide insights into human nature, which we can learn from. Sadly, lessons are seldom learnt. Civil wars, which are usually the most cruel of all, splitting families and neighbours. They are still prevalent in the world today. In my book, this is seen in the Pierrepont family, and also in the tensions between Tom and Meg. Members of these families are seen to come together at the end. Compassion and resistance to the war is shown by Elizabeth Drury and her young daughter, Alice, who learns from her example. Meg and Nick Clay show great courage when the plague hits Newark at the height of the third siege. Although these characters are fictitious, there were real people in Nottinghamshire who behaved in this way. In our own time, we hear about such happenings in places like Sarajevo and Hons. Hopefully, my book is relevant for our time. My aim is to replace the concept of picturesque cavaliers and godly roundheads with recognisable individuals, whom we might meet in the high street today. Perhaps we should all answer the question of how we would behave if there were no police force and our political parties suddenly started shooting their rivals in town halls and country markets from Cornwall to Caithness. One of the youngsters in my story sums this up on Page 54. "This isn't just a power struggle between the king and parliament. It's a struggle between people seeking power for themselves. When things don't work out as they want, they blame their neighbours, and called them the enemy. This is a sickness, formed through the war, but also fed by local feuds. This has created a weeping wound which plagues the land." Like Zachery's pots (Page 195) These who survive the war are "tested by fire" and some of them come out fine and others flawed.

You have won several awards for your one-act plays – can you tell us about one of your creations?

I was one of the six winners of an Original Playwriting Competition in 1986 run jointly by Nottingham and Derby Playhouses.

The play I wrote, "Worlds Apart", was based on the experiences of a group of Vietnamese boat people I knew, who had been granted refugee status and were then living locally. One Cambodian woman told me the story of how she had escaped with her children. She did not speak English, so one of her sons translated what she was so keen to tell me. I wrote it down, and gave her a typed copy. Later, I went on a playwriting course at the Arvon Foundation in Hebdon Bridge, where the two tutors were Alan Plater and Anthony Minghella. We had a week in which we all had to draft a play and write a scene on the same theme - "a journey". I came away with the first draft of "Worlds Apart" in my coat pocket. It was selected to be performed as a workshop production at both Derby and Nottingham Playhouses, and I had the honour of joining the cast in rehearsal with the director, Claire Grove, who later became a BBC producer. She had chosen an all black cast, which I thought was a wonderful way to make the audience feel that this tragedy could happen anywhere in the world, in any century. This was my message then and is my message still. Other plays of mine which have won an award from the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Drama Association include "The Siege of Mafeking Street", "Blow the Man Down", "Goin' Places" and "After the Storm".

What is next for you?

I am halfway through writing a saga consisting of three novels set in the future. The first of the three, "Yestermorrow", takes place fifty years from now in a country called Britannia, which has at last got the message that we cannot continue running the rat race in a world of depleted natural resources. Rising tides have swept away the town I now live in, and people have learned to live more simply in community groups, where energy is rationed as food was during the Second World War. Instead of working full-time, everyone works half-time in paid employment and half-time as a community volunteer. The community of twenty families meets on a weekly basis to discuss plans for the next week. This is not a prediction. It is a speculation of one possibility for a fairer distribution of resources across the world.

The next two books are each set fifty years on. A work in progress.