With Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 still missing without trace, Damien Lewis reveals how shockingly easy it is to make an aircraft disappear …

Damien Lewis

The C47 Skytrain - the classic, twin-engine WWII-era transport aircraft, called the ‘Dakota’ in RAF service - had lain in the elephant grass for almost two decades. It had been abandoned by the T'chadian Air force, in N'Djamena, T'chad, in north-eastern Africa, having been judged beyond repair or fit for any further useful service.

The Tchadian Air Force Colonel smiled when Mike Snow, veteran British bush-pilot and former SAS man, paid for the aircraft. ‘Vous êtes un peu dérangé Mark,’ he remarked. He always made ‘Mike’ sound like ‘Mark’.

‘Oui, mon colonel, il est à prévoir, car j'ai été élevé à Shelfield.’ Snow’s private joke: he was predestined to be crazy, having grown up in Sheffield.

Snow had flown in his trusty mechanics, Kema and Zorro, from the Congo, and together they set about getting the C47 flying again. They labored for months to make right the years of neglect. It was summer and temperatures topped a blistering 40c most days. On others, tropical downpours soaked them to the skin and prevented work on the aircraft.

There were three other derelict C47s lying on the airstrip. Snow had purchased them all as a job lot. The three were cannibalized for parts: a wing from one; a rudder from another; precious instruments taken from all. Magnetos were refurbished on a makeshift table set under the shadow of the fuselage, as were so many other components that had lain idle for decades.

Every cylinder from each of the two engines was removed with infinite care - so that’s twenty-eight in all - and soaked in a 19:1 molasses and water mixture to remove corrosion. The bores were honed to give a working surface, and pistons were treated in the same manner. Luckily the Tchadian Air Force still had a few batches of C47 piston rings in stock, ones that had been lying around for an age and were still usable.

Many times Snow offered thanks to Mr. Donald Douglas, and Messrs Pratt & Whitney for designing such durable machinery. They replaced the diaphragms in the carburetors from Air Force stock that was out of date, but still pliable. Snow altered the latch plates by opening up the orifices, to give a richer fuel-air mixture, as there was no Avgas (aviation fuel) available, only car fuel, and that was of dubious quality. The main orifice was opened up by a few thousands of an inch, to allow more fuel to pass into the engine, keeping it cooler on the lower octane car fuel.

They drained the engine oil from all the other C47s, heating and filtering it many times over to remove any contaminates, using a makeshift rig cobbled together from salvaged parts. While they slept, it warmed and filtered the oil repeatedly. In the end they had 150lts of clean oil to which they added some new oil purchased from the local market.

They replaced the aircraft's - long-dead - batteries with truck batteries bought at the local market, and for a tenth of the price of genuine items shipped in from the USA. The batteries were bolted into the aircraft’s cockpit, so that Snow and crew could keep a close eye on them during flight.

The day of the first start-up of the engines drew a large crowd of Tchadian Air Force personnel, but they kept a wary distance. According to Kema and Zorro they were convinced there was going be a large explosion, which would consume aircraft and crew. They were to be disappointed when both engines ran like sewing machines.

Many engine-runs and small adjustments later Snow was satisfied with their performance: the Pratt & Whitneys at least were ready for flight. The radios and avionics were shot completely, so those would need to be sent to South Africa to be fixed. Each time Snow spotted a South African aircraft arriving at the airport, he’d ask the captain to take an item for delivery to his radio specialist in Johannesburg, who would arrange delivery back again.

To avoid problems with the local Civil Aviation Authorities regarding the fuel, he was careful to purchase it from the local gas station using “Avgas drums” -ones that he’d created with a few cans of spray paint and some lettering stencils. For all who were observing, everything looked as though it was above board and for real.

The C47s registration documents were apparently from Burundi as was the insurance certificate. It truth, they were courtesy of the wonders of Microsoft Publisher. Snow would have to carry out a test flight prior to departure, so he arranged it for a Friday afternoon when most would be at the Mosque, and only skeleton staff at the airport. He had no First Officer, as his funds didn’t stretch to that, so Kema magicked up a Congolese ‘License de Co-pilote’ with a DC-3 endorsement, again thanks to Microsoft Publisher.

Snow knew the aircraft well enough to handle it alone, but having Kema in the right-hand seat took a little pressure off … and pressure there was aplenty. He did not sleep at all well on the Thursday night, tossing and turning and waking and dozing off to a world of system failures and single-engine-flying over crowded streets.

Midday Friday saw the C4 lined up ready for its ‘test flight’. It was 42 degrees and all were all drenched with sweat. It ran off Snow’s hand in rivulets, as he advanced the throttles to take-off power and released the brakes. Kema and Zorro had been briefed to be alert to even the minutest fluctuations of the engine gauges during the take off run, and to warn Snow instantly. The time to have engine problems was while still on the ground.

The noise was at crescendo level as the C47 lurched ahead and gathered pace.

Kema called out the speed indicators: ‘Fifty knots and rising … Fifty-five knots … Sixty knots … V One! Sixty-five knots - rotate!’

‘V One’ signifies the speed at which take-off can no longer be aborted; suddenly, like or not, they were airborne. Snow lifted the undercarriage, went to climb power and the C4 clawed into the skies. He ran his eye across the instrument panels: thankfully, the engines were operating well within their safe limits. They pulled away from the town with the hot and humid air still muggy in the cockpit, and despite the windows being fully open.

Saturday they took the first day off in a long time. They drank beers for the first time during daylight, talking of nothing but the test flight and the excitement it had given. They slept like the dead all afternoon. Monday they were back checking for problems that may have manifested during the test flight, but found little to worry about or adjust

Snow feared the test flight would cause an adverse reaction from the very people who had sold him the aircraft as junk and scrap. Jealousy and face saving would be at the fore of their thoughts now. He reckoned they should leave as quickly and quietly as possible, and before someone came up with an excuse to block them, or worse still t confiscate the aircraft. Such things happened all the time in Africa.

The spares were loaded pre-dawn Tuesday morning. In full view of everyone that was awake at that time, Snow taxied out, lined up and took off without filing any flight plan or making radio contact at all. Frantic calls from the control tower went unanswered, as he set a course southeast. After ten minutes the calls stopped and Snow was left in peace to charter a route home. No one had noticed that the C47’s tail number had been changed to a Congolese one: 9Q-CTS.

Each plane has its aircraft registration stamped onto the rear half of the fuselage, made up of a series of letters and numbers. The first two figures denote the country of registration of the aircraft, while the last three are its unique registration number - similar to a license plate for a vehicle. ICAO - the International Civil Aviation Organisation - allocates every country a unique prefix: so C is for Canada, N for North America, G for Great Britain, B for Burundi, and 9Q for the Congo - as in Snow’s 9Q-CTS.

In theory, anyone seeing the tail number would be able to trace the owner-operator, plus its country of registration.

Snow’s born-again aircraft also now sported a data plate - courtesy of the Njamena airport workshops - which corresponded with the tail number. Every aircraft comes complete with a VIN number - a unique serial number - stamped onto the data plate, which is displayed near the door. Snow and crew had cobbled one together and bolted it to the doorframe.

So ‘9Q-CTS’ was born again.

From here on in this aircraft would be invisible whenever and wherever required. The original 9Q-CTS had died in a cataclysmic crash in the Congo jungle, one that Snow and crew had been lucky to walk away from. It was a total write-off, and recorded as such on all airfreighter registries. Only now the seemingly impossible had happened, and 9Q-CTS had taken to the skies once more.

Snow had the perfect ghost aircraft with which to fly ghost missions - and sanctions-busting ghost cargoes - across Africa’s warn-torn skies.

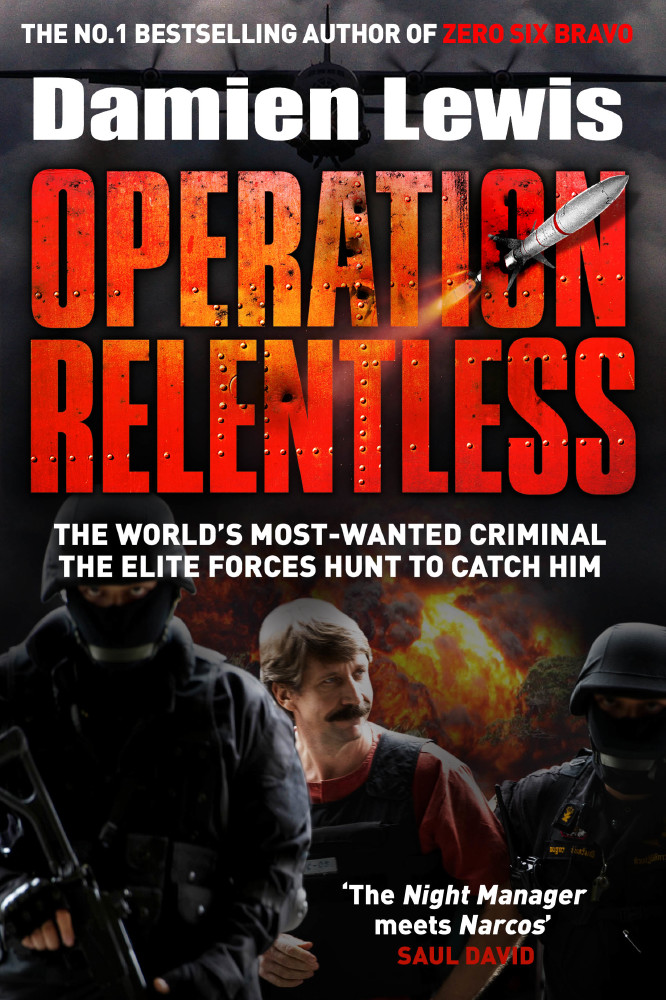

The full story of Mike Snow’s bush-flight adventures, and his role in an explosive DEA operation to hunt for the world’s most wanted arms dealer, is told in Damien Lewis’s new book: Operation Relentless, Quercus, 18th May.