It was only in 1967 that love-making in private between two men over the age of twenty-one became legal in England and Wales (although not for Scotland until 1980, and for Northern Ireland not until 1982). How, I wondered, had the denial of this right persisted for so long, when it had been enjoyed by men in many European countries, France and Italy to name only two, from way back in the nineteenth century. How had England become the glaring exception to the spread of such enlightenment?

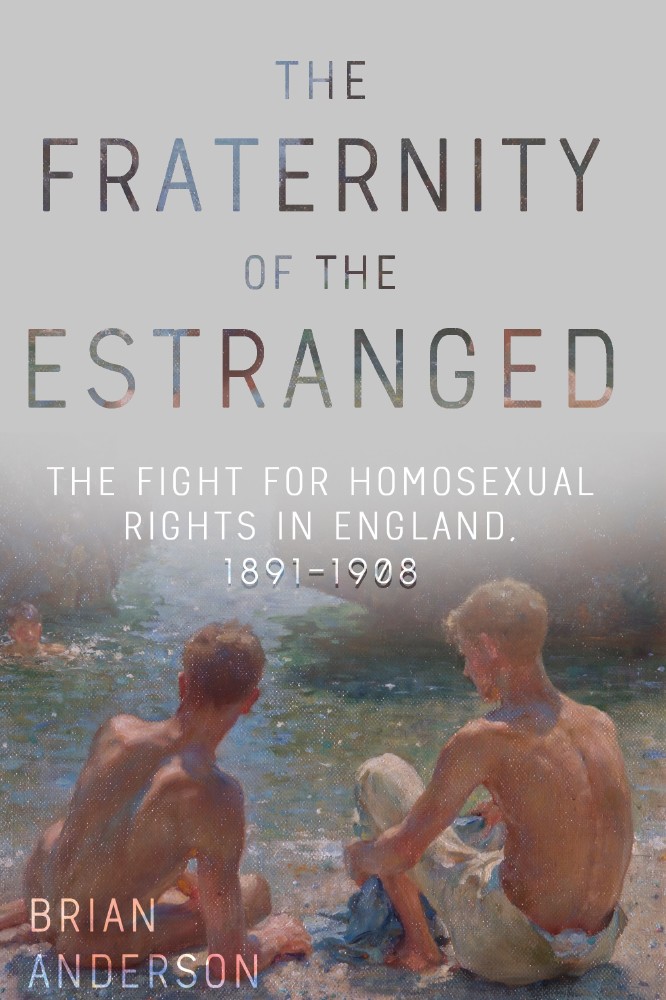

The Fraternity of the Estranged

A little digging revealed that this prohibition on homosexual love had come about during a bout of moral panic in the mid-1880s, over female prostitution, particularly the exploitation of young girls. Campaigners succeeded in having a law passed that raised the age at which a female could consent to sexual intercourse. It was during the passing of this legislation that a rogue member of Parliament slipped a five-line clause into the bill that had nothing to do with female prostitution. It made any kind of endearment between two men, even an innocent kiss, in public or in private, potentially a criminal act of ‘gross indecency’. It carried a prison sentence of up to two years with hard labour, and once inserted into the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act would remain in place for 82 years and entrap countless individuals.

Men who loved men were pushed to the margins of a society where masculinity was strenuously upheld, but I wondered what resistance there had been to such a curtailment of personal liberty? Further research revealed, to my surprise, that the law had been challenged by two upper-class homosexual men, Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds. They had set out in life as young university dons and seemed the least likely of individuals to court notoriety as defenders of same-sex love. There was a story to be told here .

Although my book shadows contemporary research on homosexuality, my motive in writing it was to bring the lives of these men out of the academic ‘closet’. As an important, but neglected part of our gay history, I wrote it primarily for the LGBT community, and, at a time more accepting of sexual diversity, hopefully, for the enlightenment of a wider public. Through a synthesis of history, biography and textual analysis, their full story is told. I trace their tortured lives, the writing of their ground-breaking books, and offer a glimpse of what it was like to be homosexual in late-Victorian England.

Last year marked the fiftieth anniversary of the decriminalisation of sex between men in private. It also saw the final act in this history of oppression, when individuals who had been cautioned or convicted under the 1885 law, the dead and the still living, were pardoned. Legislation was also initiated in Scotland for the same purpose. It has become known as the Alan Turing law, after the renowned code breaker and computing pioneer, who, following his conviction for gross indecency in 1952, tragically, took his own life.