Well, it sure ruined my day when life emptied my workshop all over the floor. I was looking in my tool cupboard for a medium-sized chisel so that I could finish off what I was making, but instead I pulled out a cardboard box. Loose photographs and a fragile album toppled to the floor. I piled up the loose pictures, put them back into the box and lifted it on to the work-bench.

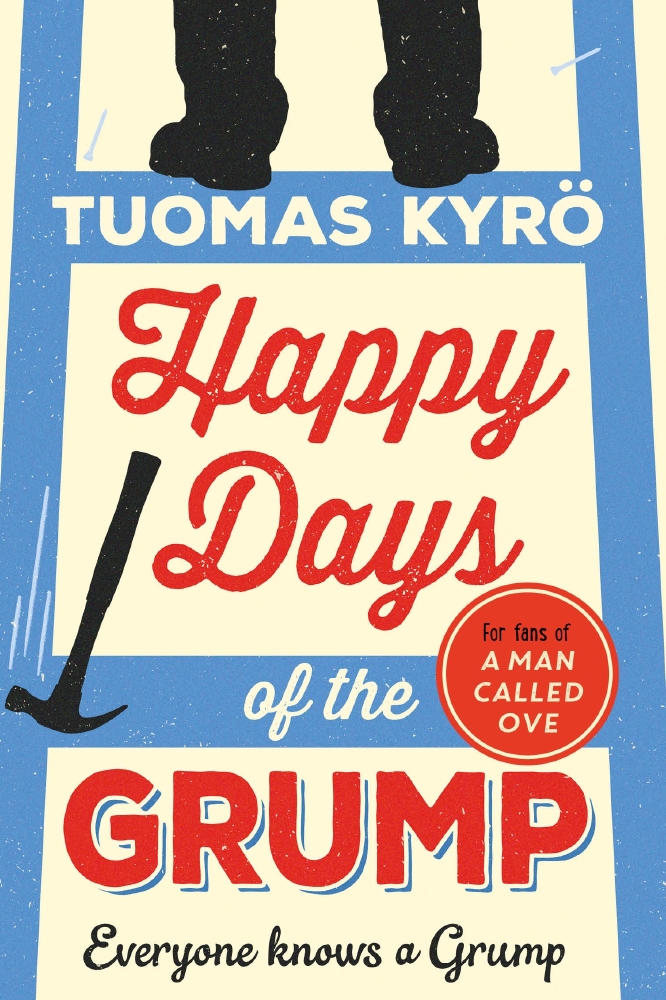

Happy Days of the Grump

I had decided that it’s pointless to look at old pictures; I remember what I remember of this life. I put the important pictures on my wall, the ones of people I admire – there are two of them; an Olympic gold medal-winning javelin thrower and a news anchor. That’s enough for me. Anything else is superfluous and can stay in the cardboard boxes or bureau drawers.

But I had to take a little peek in the album.

On the inside pages, I found my father’s name, written in fountain pen, and the date 1913, and all of a sudden I remembered looking through the album’s six pictures as a little boy with my mother in one of the brief moments when there was no work to do between tanning leather and cleaning fi sh. Between someone being born and someone dying. I also remembered my father wondering what kind of a job being a photographer really involved. At the bottom of each photograph was the legend Photographer K.R. Åkström and what I knew about him was that he spoke a strange kind of Finnish and, in addition to photographic equipment, sold little bottles of spirits during the years when alcohol was nowhere to be found.

In the first photograph in the album, my father and my mother stand side by side, newly engaged, although they looked as if they had been photographed for the state police archive. Behind the smiles they looked scared. It sure wasn’t easy in those days to get married or to pose for the camera.

Then came a picture with me in it, in my mother’s lap. Twenty-five-year-olds in those days looked different from today. My mother wore a scarf on her head and clothes almost as heavy and drab as life itself. In addition to me, there was an older child – how could I have forgotten him? Urpo, the neighbours’ orphaned child was living with us until he was old enough to work. In the picture, Urpo looked like a miniature adult, although he would have been six years old at most. Next to us is a sapling a little shorter than orphan Urpo, planted by my father the day I was born. The oak still grows today in my garden, so big that my son Hessu, Dr Kivinkinen, and the social worker all think it should be felled at once. They are scared it may fall on to the house. But it won’t fall until I cut it down and even if it did, a good house couldn’t have a better ending.

The last full picture in my parents’ album was of a completely unfamiliar person sitting in the back of someone’s horse-drawn cart. I sure couldn’t say whether it was a week day, a festival or a funeral. The very last picture was a half-picture. It was a picture of a man and a woman, holding each other’s hands. The photograph had been torn so that the faces were missing, and in the bottom right-hand corner was a stain.

There was another flash in my memory. My father had brought the picture back from the war and the stain was blood. I sure don’t know what a photograph like that was doing in our family album. It really is better that nowadays you can make friends from other countries by exchanging letters, not bullets. Beside the loose photographs I found an envelope marked ‘Important’. Inside was an entry ticket for the Salpausselkä games, a Middle Finland–Kajaani timetable, but best of all, the newspaper cutting with my father’s mother’s death notice and my father’s fiftieth birthday announcement next to it. There was only a week between the two events and my father had taken the notices to the newspaper office at the same day, thinking he might get a discount for placing the two orders at the same time. In fact, all that happened was that the two texts changed places. Granny’s death notice read: I will not be Celebrating.

Father’s birthday announcement read: Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God (Matt. 5:8). I closed the envelope, put the album into the dresser drawer and began to go through the loose photographs. Pictures from different dates were randomly mixed together, black-and-white and colour, large and small, school photos and passport photos. I looked at my wife as a young girl, before we met. She was smiling in her summer clothes, just as I always remember her. Light and feminine, even when she was tormented by the mosquitoes in the cloudberry bogs or by the varicose veins in her legs.

Now, as I looked at the old photographs, I felt as if I had stepped into them. I sure was amazed when I suddenly remembered the itchiness of woollen socks against bare skin, and the feel of my wife’s hip when my hand touched her while a family photograph was being taken. The fog disappeared before my eyes. The present day disappeared. I wasn’t looking at the photographs from today, but from when they were taken. At this age, long years and slow events are like flashes of lightning. You can’t take anything with you, and nothing much of yourself remains here. That’s why you should be able to go exactly as you wish, and who else knows what I want?

The telephone brought me back to reality. It was half-past seven, the time when my son rings. Every morning at the same time he checks that I am OK, what I have done, what I’m going to do. I pressed the green button on my phone and announced that I had been going through the lives of my parents and of myself. I knew what I had to do today, and I would do it quickly. I had to go to the care home, the fabric shop, the hardware store and to buy some ink.

Extracted from Happy Days of the Grump by Tuomas Kyro, published by Manilla £7.99