The eighteenth century was was a man’s world and any woman who wished to succeed as an artist had to overcome numerous obstacles. In a society in which women were required to marry, reproduce, and conform to rigid social conventions a professional artist risked becoming an object of gossip and hostility. Nevertheless, for a woman who had charm and good looks, was ambitious, and allied talent with hard work, success was attainable. Author Caroline Chapman examines the careers of some of these more fortunate women in her new book Eighteenth-Century Women Artists. Here she shares 10 interesting facts with Female First.

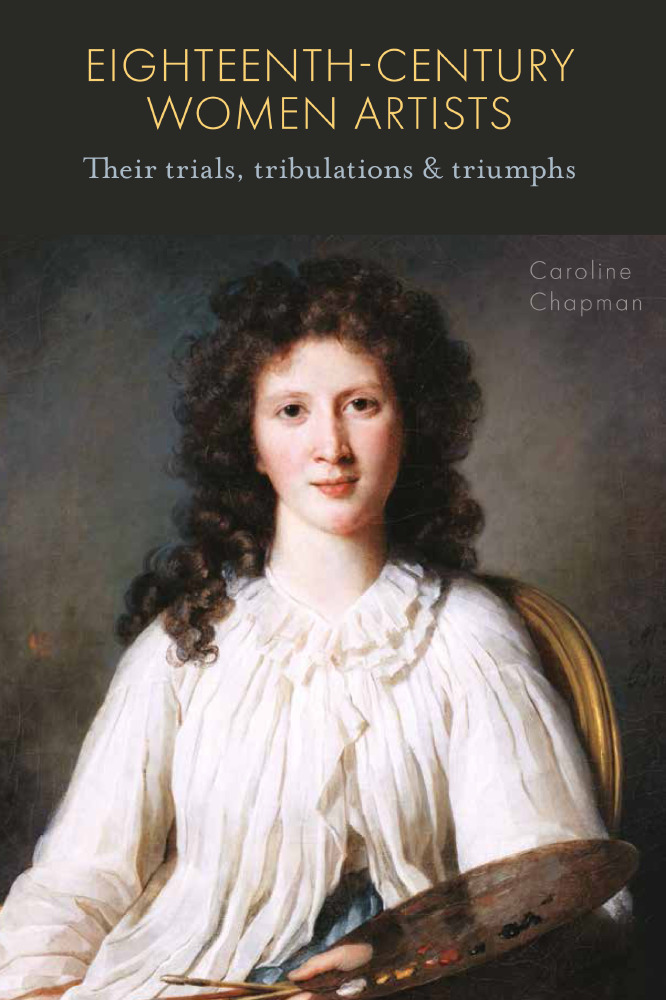

Caroline Chapman

First and foremost, an eighteenth-century woman had no business being an artist. She was put on this earth to marry and so her early years were spent developing her charms and appearance so that she could catch a rich husband.

Her education, such as it was, was tailored to enable her to become a good wife. She could acquire ‘accomplishments', such as needlework, singing and playing a musical instrument as these enabled her to shine in the drawing room. She could also paint, but on no account must she take painting too seriously or become good at it.

If a woman persisted in her ambition to become a professional artist, she was faced by major obstacles. The first was that no art schools for women existed in the 18th century. The only way to learn were either to pay for private tuition, or to learn from a parent who was an artist or craftsman.

Another major obstacle was that it was forbidden for a woman to learn about human anatomy by studying a nude - or even partially nude - figure of either sex. The only way she could learn was to copy classical sculpture or Old Master paintings.

If she had managed to find someone to teach her and had reached a good enough standard to feel able to sell her paintings, she was then faced by society’s censure of a woman who threw modesty - a precious feminine attribute - to the winds and displayed her work in public.

When assessing a woman’s work, men found it hard, if not impossible, to judge it objectively. Either it displayed all the faults they expected of her sex, or, if the painting impressed them, they promptly declared that she painted like a man!

If a woman had received private tuition from a male artist, it often fatally affected her artistic identity. She was accused of copying his style, or her paintings were assumed to be by him.

If a woman artist was both successful and physically attractive, she would constantly have to prove that her success was due to talent and hard work and not to her feminine charms.

It was assumed by the male art establishment that women lacked ‘genius'; that all their creative power went, or should go, into rearing children.

A major factor in the lives of successful women artists was their ability to focus their time almost exclusively on their careers. They either remained single, married for convenience, or married late in life. Very few of them had children.

Eighteenth-Century Women Artists: Their Trials, Tribulations and Triumphs, by Caroline Chapman is published by Unicorn, RRP. £20.00 - www.unicornpublishing.org