It’s difficult not to become infused with a sense of history when you’ve lived in Edinburgh. But if there was a single experience which had the greatest impact on the writing of Some Rise by Sin it would probably be a visit to Mary King’s Close.

This was many years before the venue became a commercial concern and back then few even knew of its existence. Some of you will know this is not your average slice of shortbread Old Town Edinburgh but an authentic 17th Century close preserved in time. Instead of a new velocipede lane, the council of the day decided to construct a new Royal Exchange and, for that purpose, chucked all the residents out and built over the top of an entire street, effectively sealing it for a couple of centuries beneath the Royal Mile.

Once below, in the dim and spooky glow of a jury-rigged lighting system it was possible to see that some of the rooms still retained their original wallpaper. High above one particular chimney-breast we were able to make out a small ragged hole in the brickwork. This, I was informed, was where a child sweep had become stuck up the flue and had to be dragged out, a fairly commonplace incident in those days. It was not known whether he survived. A compelling slice of micro-narrative.

For me, that is the true fascination of history. All lives are extraordinary, even the smallest ones, perhaps especially those. This is the stuff that interests me and essentially what I have tried to capture in Some Rise by Sin – the lives of the poor, their loyalties, loves and struggles to survive in a world which constantly contrives to drive them down. Specifically, I’ve attempted to explore how individuals might retain their principles and an essential decency in a fundamentally immoral environment. To that end my trio of main characters are a pair of ‘resurrectionists’, good(ish) men in a bad job, and the street artist, Rosamund.

Of course, there are a good many fine Regency heroines in literature, but not so many, I would hazard, from the underclasses. And this, I hope, is what makes Rosamund compelling.

Rosamund, we discover, may not be her real name but she will answer to nothing else since she enjoys the notion that rosa mundi is latin for rose of the world. Nor, like other pavement artists, will she render her chalk tableaus on a tarpaulin so that they can be reused. They must be produced afresh on the pavement each day if the few coppers she receives are to be rightfully earned by her own effort. She’s a woman of principle and resource, and so she needs to be since the period (late regency) was not kind to females of limited means. As the daughter of a printer, she was raised surrounded by the written word. Her father, however, succumbed to the smallpox, at which point creditors and attorneys converged to leave her destitute. A scarred survivor of the disease herself, she now makes her way in the world by selling paper roses on the street and through her pavement art. She may be down but she’s not out.

On the hunt for a unique cadaver, believed by the anatomists to be that of an hermaphrodite, the three protagonists are soon drawn into a dangerous world of secrets and treachery from London’s salons and townhouses to the rookeries and gambling dens of its grimy underbelly.

Although her companions are tough, opinionated, streetwise men, Rosamund is no wilting violet and no slouch herself in the ways of the streets (Reader, I worked the lucifer lay [a hawker's scam] on him), more than holding her own by means of her wits and resourcefulness. Indeed, it is she who ultimately provides that moral compass which enables them to navigate the maze of complex and perilous predicaments along their path.

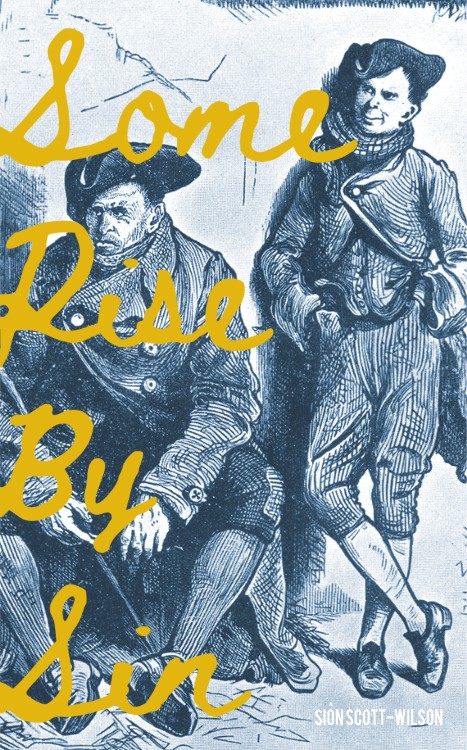

Some Rise By Sin by Siôn Scott-Wilson (Deixis Press) is available from all good retailers: https://bit.ly/SomeRiseBySinSSW.

MORE FROM BOOKS: Seven things readers might not know about me, by Imogen Matthews