What can readers expect from Born Bad?

Born Bad is a history of original sin! The book explores how that the idea that we were born both bad and guilty has become deeply ingrained in Western people not only in the past, when religion was powerful, but through to the present day. I see original sin as our culture's creation story. It comes from a distinctively Western take on the story of Adam and Eve that was first formulated about fifteen hundred years ago. This taught that every baby was born a sinner because they had inherited the sin of the first humans. In turn this meant that we were condemned by God however innocent we were or however good we tried to be. Every single one of us, whether one day old or one hundred years old, needed to be saved by Christ. Of course this religious idea, even among Christians, is not doing too well these days when almost everyone believes in the innocence of new borns. But that does not mean that the essence of our creation story, that there is something bad in our innate nature that we require some form of external salvation to be redeemed from, has not continued to prosper. More than half of my book explores influential thinkers in the modern world to show how much continuity there is (I even suggest that the thought of the famous atheist, Richard Dawkins, has remarkable resonances with original sin!). Most books on original sin set out to either damn or defend the doctrine. I wanted to do neither and have set out to explore the extent to which these ideas have become deeply ingrained in Western people, for good and for bad.

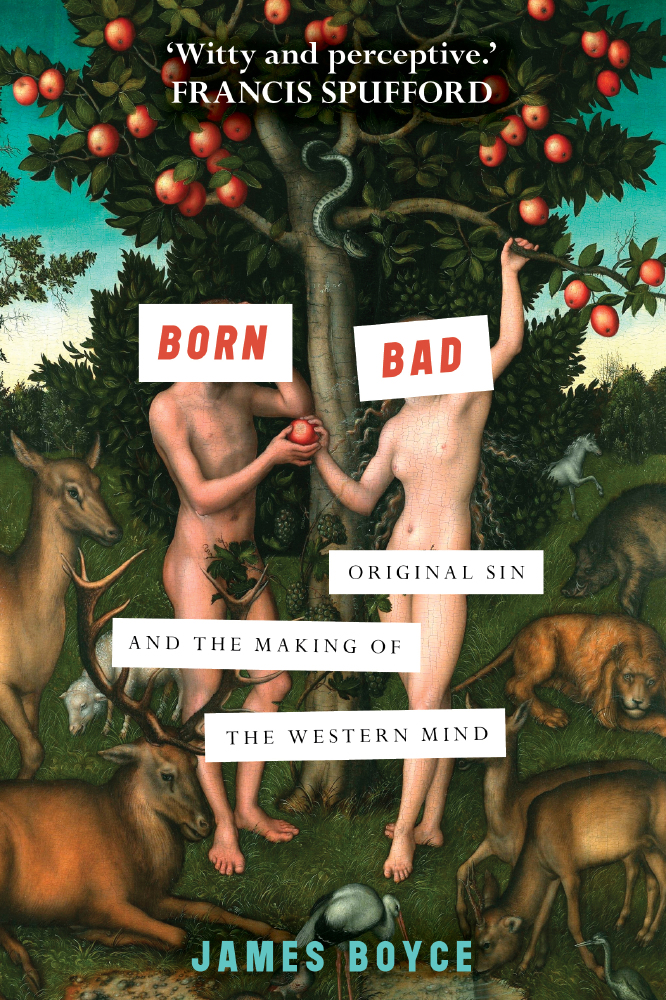

Born Bad

What did it mean to you to win the Tasmanian Book Prize and other prizes for both your previous books, Van Diemen's Land and 1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia?

I am extremely honoured to have won Tasmania's highest book prize for both my earlier books because even my fellow Tasmanian and famous writing friend, Richard Flanagan, has only won it once! Winning any prize, as Richard famously said when receiving the Man Booker in 2014, is a bit liking winning a 'chook raffle' (an Australian phrase meaning you got lucky, your number came up and you get to go home with the hen!). But I must admit that what was most important to me about winning this prize and the others that I won or got shortlisted in, was the money that came with it. I am a full time writer and it is not easy to make a living from writing history. I have a family, and when I began writing full time my children were still quite young, so I actually could not have carried on as a writer without the practical help that the prizes provided!

When did your passion for history begin?

I was recently on a three day bushwalk with my friend and publisher, Chris Feik, when we were discussing this very question. For Chris, it was when a primary school teacher asked him to imagine being one of the first settlers to come to Australia and what he would need to bring with him on the ship. Instead of just being told a list of what settlers actually brought, Chris was being asked to think for himself. Something like this happened to me at the end of high school. We had a very special teacher for just a few months, whose name (much to my annoyance) I can no longer recall. This man conveyed to me that history is not an endless collection of facts but something created by historians who immerses themselves in the context of the time. The task I was set by this teacher was to write a history of the policy of appeasement pursued by the British Government to Nazi Germany in the 1930s. I can still feel my growing excitement as I realised that there was not one answer to the question that he had set. As I read and explored the different interpretations and tried to understand the times, I realised with astonishment that if I did enough work, I could have a view of my own! I didn't put it like this at the time, but what I was discovering, under the guidance of my mentor, was that writing history was a creative process. It had important rules and disciplines, but it allowed me to interact with the extraordinary richness of the past and then form a story of what occurred and why. I found this very exciting and some part of my temperament responded to the task which all cultures have, of making sense of our past so that it can speak to the present and the future.

At what point did you decide to write about your passion and work?

Most of my life I have been a social worker (although even then my favourite ever job was working with elderly people in Norfolk - what stories of the past they could tell!). My move back to my childhood home, Tasmania in my late twenties was connected to a search for home. But I found that the histories of Tasmania that were being told did not help me understand how exiles from one island, Britain, had made home in another distant island, Van Diemen's Land (as Tasmania used to be called). The convicts, who were the large majority of emigrants to Tasmania in the first half of the nineteenth century, just seemed to be victims, and all settlers were being presented as if they did little more than reproduce a little England. I wanted to know how being in Tasmania had changed the people and my questions grew within me over the coming years, especially after I had taken a year out from social work to do my honours thesis on early Tasmania. A few years after this, when I met a gorgeous English woman on the Scottish island of Iona and started a family back in Hobart, I decided to write a book to explore all that was bubbling away within me. I must confess that the immediate spur to this was that I was far too tired and grumpy after a day of social work to be much of a husband and dad, and that the offer of a PhD scholarship to enable me to research and write, was a pretty attractive lifestyle choice! I have never lost sight of the fact that to write history is a great privilege and I give thanks every day that I have been able to sell just enough books, and win just enough awards, to keep writing (although I still need to sometimes do a bit of social work on the side which I hope helps keep me grounded!).

Who are your favourite authors and why?

Gosh, big question. I need to read writers who explore questions of meaning and connect our culture's religious tradition to the present. Writers like Thomas Merton, Richard Rohr and Dorothy Day have helped me grapple with the big questions from the perspective of my limited being!

There are some amazing writers of accessible scholarly history both in Australia and the UK who are an inspiration to me. There is still none better than the great late E.P Thompson whose book, The Making of the English Working Class, has been read by millions of people without compromising on either scholarship or passion.

I don't have as much time to read novels as I would like but of course I must mention again Richard Flanagan who is such a wise student of life and an incredibly talented wordsmith. Many of Richard's books are connected to Tasmania but he immerses himself in place so deeply that the universal longings, suffering and redemption possibilities of human existence are made transparent. A bit like the great Russian authors in this respect! If anyone has not read another of Australia's leading authors, Tim Winton, I would urge them to do so. Tim is an extraordinary writer.

What has been the response to your book so far?

Well, as you can imagine with a book connected with religion it varies! I have been very gratified by the reviews of both the American and Australian editions. One of the highlights of my writing career was the Washington Post write up by their inhouse reviewer, Michael Dirda, a man I admire very much. I get more reader feedback than most writers because to keep my privileged but marginal lifestyle going, I frequently sell my book at a big weekly market we have in Hobart which attracts tourists from all over the world. Some readers rave about the book, but some have been not so keen. In the case of the latter I think it is often because they came with a preconceived expectation of what the book was trying to achieve. Some seemed to think I should be setting out to pour scorn on original sin, others that as a person of faith myself I should be concerned to defend and renew it. When I do neither but just try to understand what the legacy of the doctrine means for all of us, they are disappointed. But of course I have total confidence in the famous good sense of readers in the UK!

What made you want to write about original sin?

Another big question that I suspect I might spend the rest of my life trying to answer!

It seems a very weird subject doesn't it. When I say it is a weird book my mum and sisters, who love this book above all of my others, get very cross at me! But I think we can all agree it is a weird subject. But then perhaps us Westerners are a weird people. What other culture constructed a God who was cross at us just for being human?! I am surely not the first to wonder if the restlessness and angst that I could see in myself and in Western culture now and in the past, including our desperate attempts to find some form of redemption from our own nature, is not connected to our very particular brand of religion. But I am the first, as far as I know, to connect this angst to our own creation story. I think being Australian brings with it a certain respect for the power of creation stories. Aboriginal Australians have taught us that the cultural power of creation myths is not dependent on their literal truth or moral veracity.

More specifically I am a Christian, and much of my life I have struggled with the way Western Christianity, in both Protestant and Catholic forms, has a tendency to present itself as a sort of club of the saved. It is quite arrogant I believe to make claims about who is and is not acceptable in God's eyes but that is what we seem to do over and over again. I think my book was partly a search to understand the source of what I understand as a destructive heresy. But equally important was my reading and immersion in contemporary culture - including its celebration of free market economics, consumerism, 'self help' and so on. At the root of all this restless consumption of products and ideas seemed to be a certain deeply taken for granted but rarely explored view of the inherent brokenness of human nature.

I also can't deny that the book is probably also a reflection of a quest to understand my own limited self. When I was younger I used to think that my vague sense that there was something innately wrong with me was just a personal hangup. While there is no doubt some truth in that, now that I am in my fifties and have had so many conversations with so many different people, I know that this experience of a difficult to identify inner guilt, which is not directly connected to any action or deed, is something many people share regardless of their upbringing or their religion. My book is in part a search to understand where this might come from and the degree that is actually a shared cultural inheritance.

What surprised you most when researching this book?

Probably two big themes stand out here. First I didn't realise how sustained and widespread was the resistance to original sin within Western Christianity. It is not a new found fad to proclaim that Gods presence and loving acceptance cannot be restricted and defined by the human institution known as the Church. There have always been those who, sometimes at the cost of their lives, have proclaimed that God is with every person and the task of conversion is less about being saved from our sins than from having our eyes opened to an ever present reality of Divine love. The resilience of this diverse dissenting tradition surprised and gratified me and I wrote about it a little in the book. The great mystic, Julian of Norwich, was one of the ablest proponents of this tradition. Julian should be known to everyone in this country if only because she was the first woman to write in English - the vernacular tongue of the ordinary people. That her work was such an extraordinary and brave book that challenged the dominant spirituality of the age in order to bring comfort to ordinary suffering folk I think makes it one of this country's national treasures.

The second big discovery was the extent of the continuity between the religious idea of human nature and modern assumptions about human nature. I expected to find some similarities but the degree of this was startling to me. I think it is precisely because everyone assumes that original sin was thrown into the dust bin of history by Charles Darwin that its view of the human condition has been able to so successfully live on in secular forms.

What is next for you?

I am currently writing a history of the resistance to the drainage of the fens. My ancestors on both my mother and fathers side came from the fens and I have long been fascinated by this largely lost landscape. The more I read about how the common people resisted the privatisation, drainage and colonisation of the bountiful wetland the more I saw similarities with the later settlement of Australia. But in the end perhaps this is yet another book about my ongoing search for home!