There’s nothing quite like climbing several thousand feet in a Spitfire, with the earth whizzing below, and the infinite sky ahead. These days if you fancy a ride on a World War II fighter plane it will set you back a few thousand pounds, but for one remarkable group of women during the Second World War it became a way of life for those few dramatic few years.

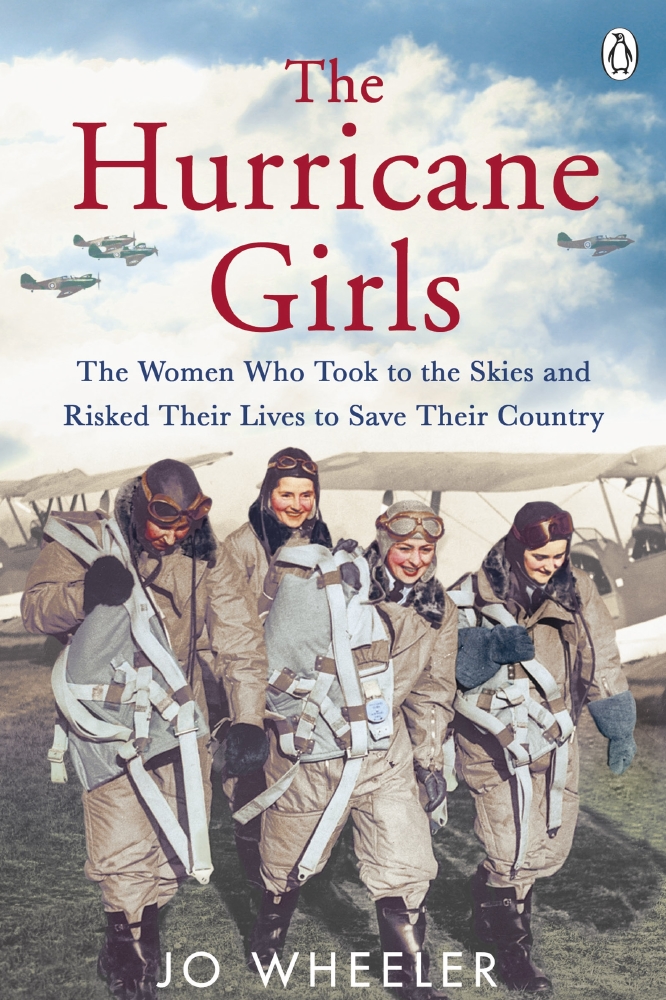

The Hurricane Girls

Women flew over 100 types of aircraft during the war, from light training planes such as the De Havilland Tiger Moth, to fast, sleek fighters like the Spitfires and Hurricanes, and the vast, four-engined Lancaster bombers. They weren’t allowed to join the RAF, but nearly 170 women worked as ferry pilots for the Air Transport Auxiliary, flying aircraft from factories and maintenance units to squadrons around Britain, helping to ensure the RAF had a steady supply of planes.

When they landed at aerodromes across the country, decked out in their flying suits, helmets and goggles, the women, known as the ‘ATA girls’ sometimes had trouble convincing those on the ground that they had actually flown the plane. Many people simply couldn’t believe a woman could handle large or fast aircraft. Some thought they’d be better off cooking their husband’s dinner or washing floors.

Since the birth of powered flight there have been pioneering women in aviation. Amy Johnson, a fish merchant’s daughter from Hull, was the first woman to fly solo from Britain to Australia. On her return in 1930 she became an instant celebrity. This was the heyday of the leisure aviator and women, usually those who had money and high status as lessons were very expensive, joined flying clubs across the country. Some had their own planes and flew to glamorous, champagne-filled rallies across Europe. When the Second World War broke out the trips to Europe stopped and the female pilots wondered what they were going to do with their flying skills.

In the 1930s Pauline Gower, an MP’s daughter from Kent, became an air circus pilot and set up Britain’s first all-female air-taxi business offering joy rides to the public from a field with her friend Dorothy Spicer. As one of the most experienced pilots in the country, Pauline felt strongly that female pilots such as herself and Amy Johnson could, and should, take to the skies for the war effort. She set about persuading the power-that-be in aviation and politics that female pilots should be allowed to join the Air Transport Auxiliary, ferrying planes for the RAF.

Dozens of women applied and initially eight pilots, who had all flown at least 600 hours, were selected to form the first women’s ferry pool in Hatfield, Hertfordshire. For many months they were only allowed to fly open cockpit, training planes. It was still thought women couldn’t handle the fast, operational fighters. During the freezing winter of 1939/40 they flew over 2000 De Havilland Tiger Moths without a single accident, as far afield as Scotland and Wales, only to have to make the grueling journey back to Hatfield on freezing wartime trains.

As the war continued, more women pilots joined the ATA, and they were eventually allowed to fly an increasing number of aircraft, including the longed-for Spitfires and Hurricanes, heavy twins like the Wellington, enormous four-engined bombers such as the Lancaster, and even a few of the new, super-fast Jet planes.

ATA pilots were often asked how they could handle so many different aircraft having never flown many of them before. They were helped along enormously by a small book of Ferry Pilots Notes, the ‘blue bible’, which had been produced to outline all the most important information about each aircraft. The notes were brief, concise and invaluable, but even with these notes to hand, it’s still incredible to think the ATA pilots managed to fly so many planes with so little training.

Over and over again the ‘ATA girls’ proved they could do the job just as well as the men. In 1943, thanks to Pauline Gower’s persistence as the leader of the women’s section, they earned the same wage as their male counterparts, making the ATA one of the country’s first equal opportunities employers.

Life as an ATA pilot could be enormous fun, thrilling and liberating, whizzing across the country at 350mph, ticking off yet another new aircraft in the pilot’s log book. It could also be grueling and very dangerous. The pilots faced many hazards: bad weather, mechanical problems, barrage balloons - the large silver gas-filled balloons which flew over sensitive areas during the war to prevent incoming enemy aircraft. Occasionally they came across a Luftwaffe plane in the sky or had a close encounter with a V-1 flying ‘buzz bomb’. Sometimes they were even shot at by anti-aircraft gunners on the British side. One plane, the Anson Taxi which carried pilots to airfields, was shot at by a Luftwaffe plane and for a while after that the Anson carried a gunner in the rear turret. The pilots didn’t have any radio in the cockpit. They flew completely alone with just a map, compass and good old-fashioned eye sight. They weren’t supposed to fly above the clouds because they had to maintain contact with the ground, but in foggy, rainy Britain that wasn’t always possible.

In the freezing January of 1941, Amy Johnson flew ‘over the top’ above the clouds, on a trip in an Airspeed Oxford from RAF Prestwick bound for Kidlington. After hitting bad snow and fog the celebrated pilot ended up miles off course over the Thames Estuary. It remains a mystery exactly what happened next, but most likely she ran out of fuel and bailed out. After a failed rescue attempt from a nearby naval vessel neither the plane nor Amy Johnson’s body were ever recovered. Parts of her aircraft and some of her personal belongings were however found floating in the icy waters.

Fifteen women pilots lost their lives as air-women during the war. Another was Irene Arckless, the daughter of a Carlisle organ builder. She didn’t have the money or status to have her own aeroplane before the war, but she managed to get lessons at her local flying club. She met another aviation enthusiast Tom Lockyer and they fell in love. Tom joined the RAF and his Spitfire was shot down over Nazi Germany. When Tom was captured as a POW spirited, plucky Irene had a mad idea she might go and rescue him. In any case, she was desperate to fly again and do her bit for the war. Despite her relatively humble background Irene managed to join the ATA, but her life was cut tragically short when a plane she was ferrying crashed into a house in Cambridge. The cause of the accident was never discovered. When Tom Lockyer was finally released just after VE Day he came home to life without his beloved Irene. [photo available]

The war was marked by loss for so many on all sides, but for the women pilots who survived the war it had also been a strange kind of opportunity. The youngest female ATA pilot, Jackie Moggridge, who had learnt to fly in South Africa as a school girl in the 1930s, remembered her time in the ATA as some of the best of years of her life. The ATA pilots – both the men and the women - played a pivotal role in key moments of the war, they flew vital Spitfires for the Siege of Malta, flew Tempests and Typhoons in preparation for the D-Day landings and some went across to the continent. Towards the end of the war the ATA took on pilots who had never flown at all and trained them from scratch.

When the conflict ended the ATA disbanded and, in spite of their achievements, many of the women struggled to get jobs in post-war, commercial aviation. Old prejudices returned, which in many ways still persist to this day. A plucky few did persevere though and they made great gains. Jackie Moggridge, along with four other women pilots, got awarded full RAF wings in the 1950s - a little-known achievement before the RAF generally accepted women. Jackie also became the UK’s first female airline Captain. ATA women became stunt pilots, flew helicopters, became captains, air traffic controllers and broke the sound barrier. Today, as people are still fighting for equal pay and, across the world, and women and girls are challenging prejudices, the remarkable women of the ATA remain an inspiration.

The Hurricane Girls by Jo Wheeler is published by Michael Joseph out now £7.99