To stroll now around where the old London docks used to be is to see very little of how it used to be. Today there is a sea of modern development, full of waterside flats and chi-chi restaurants, but at one time it was a bustling, thriving part of East and South East London, so much so that once it was the world’s largest port.

Katie King

My ‘Evacuee’ novels have the Ross family living in Bermondsey to the south of the River Thames, with the dad, Ted, a docker, and the mum, Barbara, a shopworker. Back in the 1930s Bermondsey was a noisy, smelly and lively area, with street upon street of two-up two-down terraces that housed the river workers. Many others would work at the Peek Frean biscuit factory towards the south of the borough, so large it dwarfed the surrounding streets and led to the area being dubbed ‘biscuit town’.

When war was declared in 1939, there was a mass evacuation of children and vulnerable people from cities across the land, with whole schools being sent to areas of the country deemed safer.

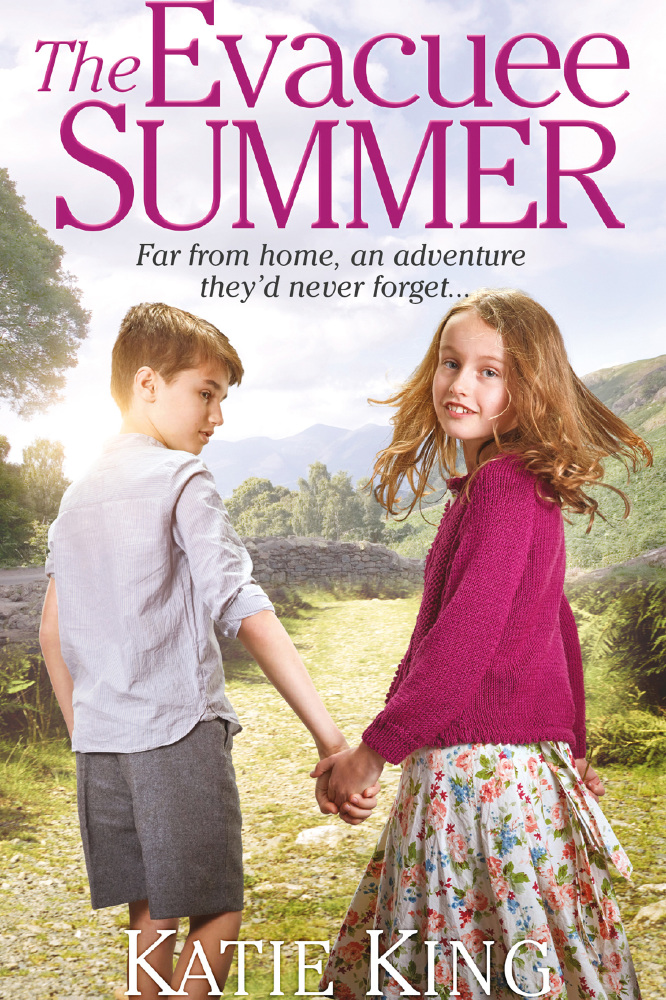

In my books Barbara and Ted’s ten-year-old twins Connie and Jessie, and their heavily pregnant aunt Peggy find themselves in the rather grander Harrogate – it would have seemed a different world to them from the narrow streets and noisy carousing in the many public houses in docklands.

When I moved to London back in 1980 I lived first in Bow in East London, quite close to the Isle of Dogs, and later in South East London. It was clear by the mass of tower blocks and post-1950s buildings that something cataclysmic had happened to have led to so much of the original housing being lost.

And indeed it had. The distinctive whorls and twists of the River Thames meant that the heart of London was easily identifiable to enemy bombers, who could simply follow westwards the folds of the water glinting in the moonlight.

Docklands was especially crucial to the bombers, as a two-pronged approach was adopted. While our merchant navy struggled through attacks from destroyers, mines and submarines trying to deliver imports to keep the country going, ports and docks across the country were bombed repeatedly in an attempt to break a crucial part of our infrastructure.

It was a successful strategy. Mile upon mile of docklands, businesses and housing was destroyed during the blitz, with a tragic loss of life.

But community spirit was strong in those working-class areas, and it survived the war. Now all of London is truly multi-cultural and vibrant, but there still remains a sense of looking out for one another – I was very struck by this when I first arrived in London, as it was something I’d not really experienced before.

Years later, when I became a writer, I began to think about this more and more. And I chose to set my novels in WW2 as it is such an interesting period in history in the social sense – class barriers were never the same afterwards, while women felt a sense of empowerment previously unknown and people got used to those from other cultures enriching our community.

I began to think about what it must have been like to let one’s children be evacuated, or to have been evacuated oneself. It would have been as nothing they could have imagined previously. It’s the small, human dramas of loss, redemption, fortitude and resilience that interest me, and this, combined with walking through areas totally unrecognisable post-war, has resulted in my Evacuee books.

I can only hope that in some small way I’ve managed to pay tribute to the hopes and fears of these brave people – both adults and children – who all took such giant strides into the unknown. Parts of London changed almost beyond recognition during this time, but the memory of those who lived through WW2 is still alive and poignant, and we wouldn’t be living the lives we have today without them.