Domestic Noir was first used to define a sub-genre of crime fiction in 2013, when Julia Crouch described it as `primarily in homes and workplaces, concerns itself largely (but not exclusively) with the female experience, is based around relationships and takes as its base a broadly feminist view that the domestic sphere is a challenging and sometimes dangerous prospect for its inhabitants.`

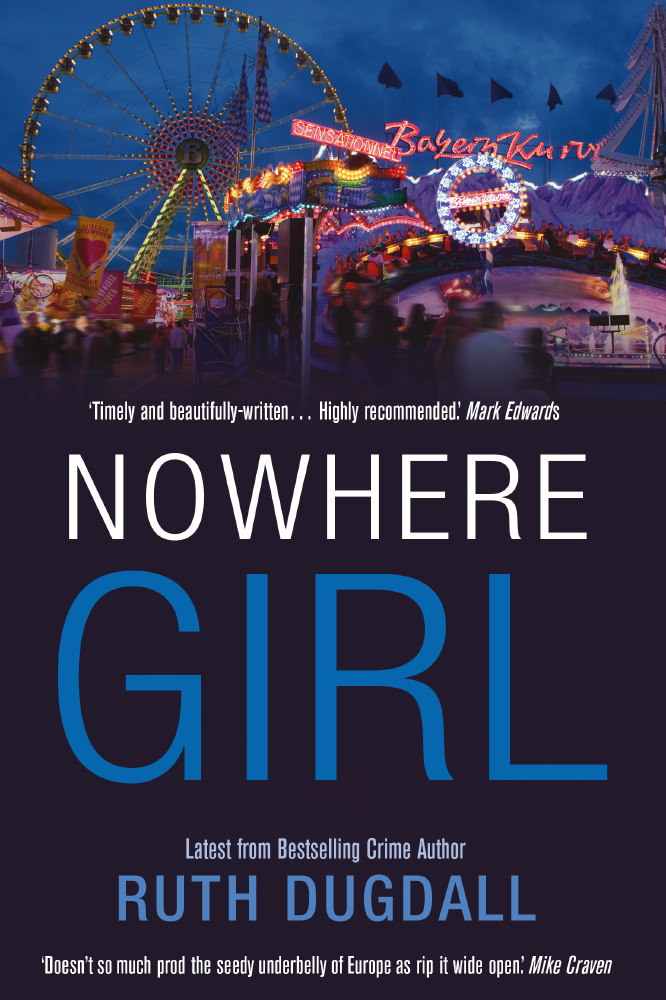

Nowhere Girl

However, novels that fit this definition have been around for donkey's years. A classic example would be Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca. What is so clever about this book, is we don't even know what kind of novel we are reading until the end and by then we are rooting for the wrong character. Don't you just love a book that messes with your head?

The Greeks loved a bit of Domestic Noir. They were obsessed with family relationships gone wrong. Think of Medea, that nightmare of a mother, rocked out of her sanity by her husband's infidelity. A parent who hills their children to punish an unfaithful spouse. Such an ancient story, yet one we see repeated in news headlines around the world…the power of domestic noir is that it is frighteningly familiar.

For as long as books like this have been around, people have tried to define them. Other definitions include the `Marriage Thriller` and `Chick Noir`. Thank goodness neither of these definitions stuck, as they really don't capture the gravitas or the scope of novels in this field. And who wants to refer to a woman as a `chick` in this day and age?

In a twist on historical convention, which would have delighted George Eliot, male writers in this sub-genre often disguise their gender by using initials.

S.J Watson rocketed to fame with Before I go to sleep, a novel with all the hallmarks of domestic noir. However, his publishers were initially coy about his gender on promotional information, worried it might put female readers off.

The current queen of the genre is Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl being a perfect example of how a flawed marriage is the perfect environment for domestic noir. But if you want to read an even better example try Sharp Objects, her first novel. Not for the faint-hearted.

Why is it so scary? Answers usually refer to the normality of the setting, the seemingly ordinary façade that often exists to hide very dark deeds. The inference is that, behind closed doors, any family can be criminal. And that is a terrifying thought, born out in how horrified we are when we discover, in real crimes, that the culprit is a family member like when the Philpott's house was burned down killing six children, or when Shannon Matthews went missing. Wouldn't we all have preferred the culprit to be a stranger?

Or the reason for its popularity may be the exact opposite; there is nothing more comforting than reading about a seemingly `perfect life` with a rotten core. Because we can close the book and feel content with our own less-than-perfect life, because at least we are safe.

For writers who identify with the label, `domestic noir` is a concise way to define their novels when `crime novel` or `psychological thriller` seem large and unwieldy. Speaking personally, discovering the term `domestic noir` was a bit like trying on a made to measure dress after years of hand-me-downs.

There will be a panel on Domestic Noir, featuring Julia Crouch, Elizabeth Haynes and myself, at Felixstowe Book Festival in June 2016.

http://felixstowebookfestival.co.uk

Ruth Dugdall is the author of five crime novels, all of which could be categorised within the sub-genre, `domestic noir`!

Her latest, Nowhere Girl, concerns a teenage girl who goes missing in Luxembourg.