Jonathan Aycliffe

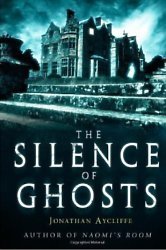

Over the years, I’ve had some great and some abysmal jackets, and happily The Silence of Ghosts is in a new design that’s just perfect for a ghost story. All my ghost stories are novel length. In fact, I’ve written very few short stories in the genre. Using the novel format gives me more time to develop character and to place my ghosts in a context. It’s much like watching a full-length film. Readers say they are biting their nails or clamped to their seats, and that can best be achieved through length and incident.

Please tell us about the characters of Dominic and Octavia.

The story is set in 1940. Dominic has been to sea with the Navy and has lost a leg. He is sent by his parents (two unsympathetic characters if there ever were any) to the large country cottage on Lake Ullswater. He takes his young sister Octavia, who is profoundly deaf. Dominic falls in love with his nurse. Octavia begins to see things.

What made you decide to take the book to Ullswater in the Lake District?

I’m not absolutely sure. I used to stay on Ullswater, at the famous Sharrow Bay Hotel, one of the best in the country. I needed a secluded place, and Ullswater still fits that description but was quieter back then. Wordsworth’s daffodils are still growing on one side of the lake.

What is it about the quintessential ghost story that is still so popular for readers and writers alike?

It’s hard to say. The real ghost story is mainly a British thing, with some input from America and Canada. So I think it helps to be steeped in Anglo-Saxon culture. I’m not a believer, but I’m aware that Christian themes and iconography play a part in this. Our weather plays a role too: the drawing in of the dark nights, mists, snowfall all contribute to a sense of shadows lurking in doorways, of sounds that can’t be identified. In the past, when there was only firelight and candlelight, people would gather round the fire to drink mulled wine and listen to tales of the uncanny.

Your work has been praised for ranking among the finest of English ghost stories, so which authors have given you inspiration in this genre?

The most influential was M.R. James, whose short stories are still the most haunting. One oddity is that James, who died in 1936, was Provost of King’s College, Cambridge, where I did my PhD. Not only that, but the college librarian, ANL Munby, produced a slim book of short ghost stories. So maybe it’s something in the College Chapel.

What frightens you the most in fiction?

Non-fiction is usually more frightening, at least the sort of things I read. In fiction, I never read horror, but I will read and enjoy classic or modern ghost stories. My favourite fiction title for a long time was H P Lovecraft’s The Strange Case of Charles Dexter, which has influence both The Silence of Ghosts and The Matrix. Good crime novels can be scary: the best are the novels of Patricia Highsmith. But I must take the opportunity that, thinking of readers of this magazine, my absolutely favourite author is the American-Canadian Keith Maillard. His best novel, Gloria, is set in a world with glamour, hot dresses, make-up, sex, majorettes, violence and intellectual exploration.

Have you ever seen a ghost? If so please can you tell us a bit about it?

I’m sorry to disappoint, but I haven’t. Not unless I saw one and didn’t know it at the time (there’s a famous story on that theme). Some years ago, at the convention of the Ghost Story Society, the chairman asked how many people believed in ghosts. The answer a resounding ‘Nobody’! People who believe in ghosts don’t understand literature or fiction, and they go to their own conventions and spend most of their time in supposedly haunted houses and bring lots of special cameras and hi-tech microphones with them. Life’s too short.

How difficult is it to avoid all the clichéd references to ghosts when writing your own brand of fiction in this area?

It’s a bad idea to ignore all the clichés when writing genre fiction. People want to see a ghost or be taken into a haunted house or to hear ghostly voices and moaning in the middle of the night or to see children who can only be dead. Without things like these, a ghost story will fall flat. Of course, the writing should be as fresh as possible. You can’t write a crime story without a crime or a love story without two lovers. If you choose to write in genre, then you have to accept its limitations. We’re not all Keith Maillard!

What is next for you?

I’m Irish, and recently I decided it was time to have a ghost story set in Ireland. I’ve written about half of it, starting out on the Great Blasket, a famous island on the west coast that was abandoned for many years and is now open again in the summer. Later, it movers up the coast, not far from the Cliffs of Moher. There’s a lot of atmosphere and some very nasty dead people in a tower. Much of that is inspired by St. Michan’s Church in Dublin. I visited their crypt years ago and have never forgotten it: coffins everywhere, mummified bodies spilling out of them, a single light bulb.