This week we’re examining the strange phenomena that is the Mandela Effect; that feeling where you and potentially thousands of others know you remember something a certain way, but you can only find evidence to the contrary. Is it some kind of mass forgetfulness? Is it a 1984-esque covert operation? Or are we constantly slipping into alternate dimensions?

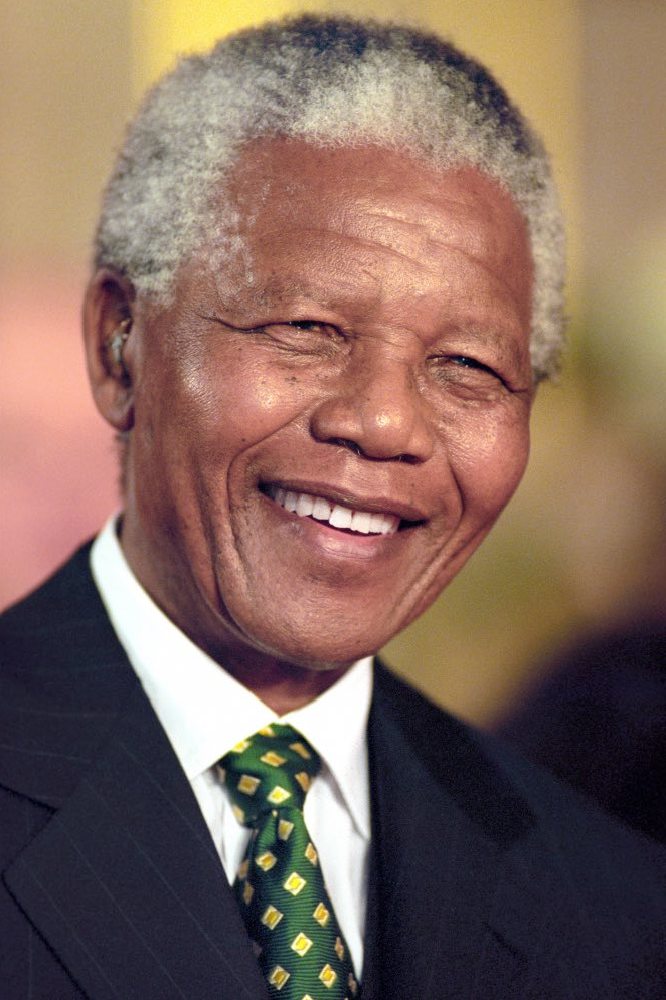

Nelson Mandela, 1996 / Image credit: Tony Harris/PA Archive/PA Images

What is the Mandela Effect?

The Mandela Effect is a type of false memory first coined by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome in 2010. The term gained traction following the death of anti-Apartheid leader Nelson Mandela in 2013, when hundreds flocked to social media to voice their confusion; many were convinced that Mandela had already died in the 80s while imprisoned.

It’s more than a case of just being mistaken; for many, they think they can actually remember visual references or news broadcasts in relation to the incident that didn’t happen, to the point where they’re more likely to believe in some kind of conspiracy than accept that they are remembering things wrong.

But there was a prominent anti-Apartheid activist who passed away in prison in the late 70s named Steve Biko. His name may have been mentioned alongside Mandela’s in news stories surrounding his death, which may be the reason why some people assumed Mandela was the one who had died.

Some popular examples of the Mandela Effect

Nelson Mandela’s death isn’t the only thing that has baffled those with false memories over the last few decades. There are some rather minor incidents which have since blown-up all over the internet.

The Berenstain Bears

The Berenstain Bears were a set of children’s picture books written by Stan and Jan Berenstain beginning in the 60s, and which would later be adapted to television. It sounds innocuous enough until we examine the fact that thousands of people actually remember the series being called “The Berenstein Bears”, not “The Berenstain Bears”.

The most likely explanation here is that “stein” was a more common suffix in surnames than “stain”, and so most people’s brains filled in the word as they saw fit before they got a chance to read it properly. Plus, unofficial merchandise bearing the incorrect name may have played a part in this collective misremembering.

Sinbad's Shazaam

Perhaps a more confusing example is the supposed existence of a 90s flick entitled Shazaam starring comedian Sinbad as a genie. People claim that they remember huge chunks of the movie and even what the VHS cover looked like. There’s only one problem; there never was a film called Shazaam starring Sinbad.

There was a film entitled Kazaam released in 1996 starring Shaquille O’Neal as a genie which explains a lot, although Shaquille and Sinbad don’t look terribly alike. There’s also the fact that in 1994, Sinbad hosted an afternoon of Sinbad the Sailor movies for TNT, wearing a kind of turban-esque headscarf that made him look a little like a genie. There was also a 1960s animated series about a genie named Shazzan. Still, there are always going to be people who refuse to believe that Shazaam never happened.

Dolly’s Braces

One of the fiercest debates among Mandela Effect researchers is regarding the appearance of the character Dolly in the 1979 James Bond movie Moonraker. She is depicted wearing pigtails and glasses, and many remember her also having braces.

However, if you watch the film back, you’ll see that of course she doesn’t have braces. Many have tried to claim that she originally had braces in the famous smiling scene but they were digitally removed for continuity with the rest of the film (where she doesn’t have braces). Others have said that the scene simply doesn’t make sense without the braces (it would intensify her bond with the silver-toothed Jaws if she did).

There are a variety of reasons why we might have remembered Dolly as wearing braces: the way she bared her teeth made them look rather prominent, we only saw them for two seconds and that was immediately after we saw Jaws’ gleaming silver teeth which makes it an easy scene to muddle in our brains, plus our perception of a stereotypical geeky girl might include braces.

The most common instances of the Mandela Effect tend to be movie misquotes; lines from films that are continually misread, probably because we know the quotes so well from other people quoting them rather than from the films themselves. I.e. It tends to be social reinforcement of incorrect quotes that creates this particular Mandela Effect.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back - Luke, I am your father.

Corrected - No, I am your father.

The Silence of the Lambs - Hello, Clarice

Corrected - Good Evening, Clarice.

The Wizard of Oz - Toto, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

Corrected - Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.

Titanic - I’m king of the world!

Corrected - I’m the king of the world!

Casablanca - Play it again, Sam.

Corrected - Play it, Sam. Play ‘As Time Goes By’.

Other explanations

While tricks of the mind and poor recollection are the usual explanations for the Mandela Effect, there have been alternative suggestions.

Slipping into parallel universes and other dimensions are often mentioned as reasons for this unusual phenomena, with some even suggesting that it could be proof of time travel. The book Rabbits by Terry Miles explores the Mandela Effect as a symptom of alternate dimensions.

MORE: Rabbits review: Terry Miles has us eager to play “the game” in his ARG thriller

In reality, it’s just your brain being an unreliable witness. It happens all the time in police reports and is known as “confabulation” - essentially, lying without realising. The truth is, it would be really hard work for your brain to consciously process every piece of information that’s presented to it all day every day, so a lot of things get replaced by preconceived ideas known as schemas; that is, your brain filling in information where there are recognisable patterns.

Yeah, it doesn’t sound quite as cool as having multiple dimensions running alongside our own, each with a different course of events. But the fact that we are so easily manipulated by our own unconscious assumptions makes for an interesting basis to a number of social issues we have today.

Tagged in Nelson Mandela bizarre Movies