Between 1989 -1994 I took my annual holidays by travelling around Brazil in public buses. Ostensibly I was investigating Cordels, street ballads composed and performed by folk artists. But I had other objectives. As an epidemiologist I was scouting for possible projects that ought to interest medical charities. I wanted to reach the tributary of the Amazon that Theodore Roosevelt discovered with General Rondon. He called it The River of Doubt because even when it was put on the map he wasn’t sure that it was the river he was looking for. It has been since named Rio Roosevelt. But above all I wanted spend time with Brazilian friends and colleagues that I knew only by letter.

Margaret

After my fifth and last visit I published a book on the Literature of the Cordel (Lampion and his Bandits, Menard Press, 1994). My medical quest came to nothing after several misadventures that taught me more about the country than perhaps I wanted to know. I got to the vicinity of Rio Roosevelt but was never sure if I actually saw it. Immersing yourself in the fifth largest country in the world, a veritable continent, for five months, is to lose your bearings, and you find what you find.

I thought I knew Brazil until I went there. I expected to be overwhelmed by the natural beauty, and I was. Colour was almost a physical presence and vegetation a spiritual one. The brutality of the cities had a perverse beauty too. The coast and interior of the North East engaged me most. Recife and Salvador where the three dominant cultures of Brazil come together, Indian, Portuguese and African. In the interior I was particularly drawn to the semi-desert of the sertao which nurtured an astonishingly rich history of revolts, and literary and musical culture.

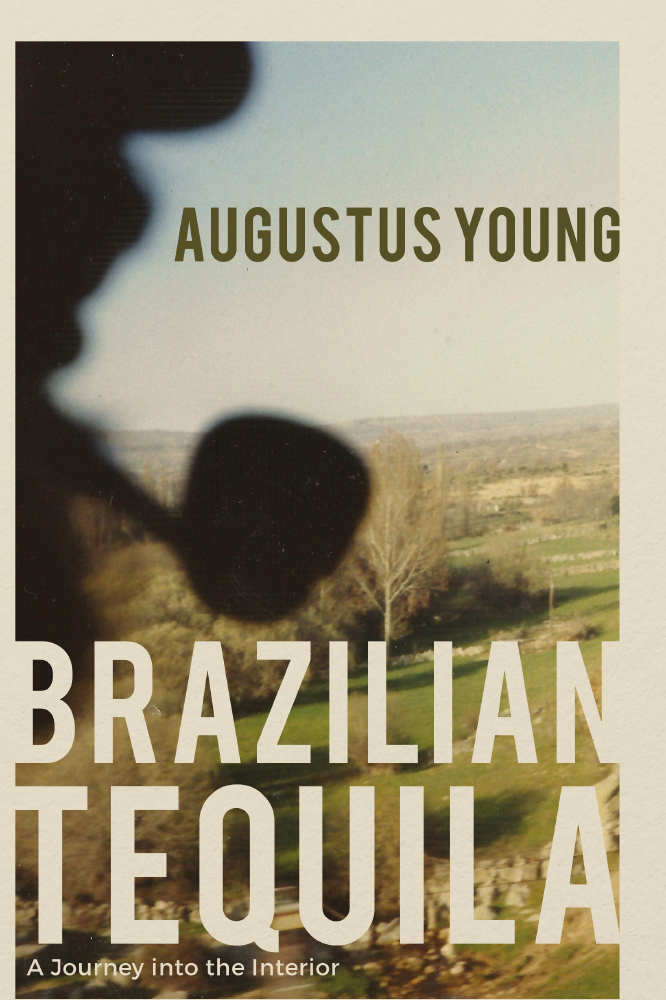

But there was a worm in my bottle of Brazilian tequila. The more I came to know and love Brazil the less I understood its cynical politics, and how it trickled down to my friends in the middle classes. Public corruption and private idealism went hand and hand. At the time I felt Brazil's moral universe was worlds apart from Europe. It was only in retrospect that I began to reconcile them, at least for my friends.

On my return to London I edited my diaries into a book that I entitled ‘The River of Doubt’. It included descriptions of places and people I mixed with on extended journeys. But my moral doubts born of an European education kept intruding and the final chapters were a self-righteous rant. My fellow traveller and partner, Margaret, laughed when she read it. ‘Is that what you were thinking when you were enjoying yourself’. As a good Scot she appreciated the canny in the survival mechanisms in a country too large and vital to abide by a common law. Meanwhile, the present would have to look after itself as best it could. Indeed, In our time there Brazil was moving from a military dictatorship to a rather tentative democracy. The just society was on the way, but it had long way to go.

I put my manuscript aside, and only returned to it by accident. In 2012 Margaret died and, after forty-two years together, I needed to reorder my life. Searching her laptop for tax information that I had mislaid., I found a file named ‘Brazil’. I copied it with her tax file. Two weeks later the laptop was stolen, and I was moved to open ‘Brazil’. It contained my ‘River of Doubt’ heavily edited to exclude herself.

The deletions were made seamlessly. And my moral rants (unanswered by her mollifications) stood out as laughable.

Excluding herself was wise. I could never write about Margaret convincingly. We were too close, and that closeness in the writing came between me and Brazil. I remembered how happy she was there. The dry-heat of the sertao suited her, and she learned to ride a motorbike in the jungle. I knew I would be obliged to work again on my abandoned manuscript. I would bring pleasure back into it. Nevertheless, I couldn’t efface the reality of my experience. My European imperatives, and interior darkness, were part of it. I resolved to write about Brazil, worms, wonders and all. However, I restored Margaret to the narrative with the photos she took with a box-camera.