Big Appetites: Tiny People

Big Appetites is a new photo / humour book which features my fine art photographs of tiny figures shot in real food environments. Each image is accompanied by a caption that is designed to reinforce the humour and action in the pictures and to give each character a bit more of a story arc. Though some of my photographs have been widely published in newspapers, magazines and online, this book contains a large body of new work shot specifically for the book and is the largest collection of photographs ever compiled in one volume.

Where did your inspiration for these pictures come from?

I’m sure the original inspiration was in all of the media I was exposed to as a child. Cinema, television and advertising were surprisingly full of the concept of scale juxtaposition. In fact, it is still a device that is used a lot now. It’s surprisingly common not to mention adaptable. The same concept suited Jonathan Swift in 1826. And if you consider how most museums are full of tiny artefacts, mankind has been fascinated with miniature things for tens of thousands of years. As a child I was an avid collector of Matchbox cars. I loved building scale models too. I think as children we’re especially adroit at working out scale issues because we live in an adult world that is out of scale with our bodies and we’re constantly playing with a constellation of toys that is even smaller than we are. So perhaps it is something that is wired into us.

In a more contemporary sense, I saw an exhibit of the Chapman Brothers’ work at the Saatchi gallery in December 2002 which used figures in large scale dioramas. And around that time I also saw the Travellers by Walter Martin & Paloma Munoz and was inspired by the dark tone of their scenes, set with scale figures inside snow globes. I went home to New York and made the very first of my food and figure images and continued to work on them for years. The photographs were first syndicated in the UK and went viral in 2011. In the time since I’ve become aware of a number of other artists doing parallel work, which doesn’t surprise me at all considering how accessible the elements of toys and food are in all cultures, and how common it is in the art world for artists to independently explore similar ideas.

Why is it important to you that we look more closely at the intricate and extraordinary world around us?

Because to do otherwise, to ignore the marvellously complicated and elaborate world around us, would be doing ourselves a disservice. I think this is more important now than ever in an Information Age in which we’re being bombarded with stimuli and our coping mechanism is to filter most of it to some degree. Much of our consumer culture in the Western world also is designed to conform to our expectations. So in a way everything becomes a devalued currency and only the things that surprise us and exceed those expectations make it through. Every time we pour a glass of wine and stop to smell and taste it carefully, we’re making an excuse to engage our senses more fully. That’s but one example of how we can be more mindful about really savouring the world around us and looking more closely. The most amazing things are subtle, nuanced and easy to miss.

Please tell us about your photography background.

I’ve actually always considered myself more of a writer. But that’s probably because when you’re a child people are more likely to put a pencil in your hand than an expensive camera. I definitely made a lot of visual art as a child and adolescent. I was actually kind of obsessive about it. When I was about 15 I got a camera for my birthday and proceeded to take about 30,000 bad pictures from that point on. Eventually I figured out what I was doing. I never really had any formal training as a photographer. I shot some pictures as a high school journalist and then later at university too. My last year of university I founded my own commercial photography company doing event photography for all of the sororities and fraternities at my school. That was great training because it taught me to work fast, often in the dark, loading film by feel. I think the way I arrived at the point of actually making successful photographs was simply that I kept at it and didn’t give up.

How long did it take you to pull all of these photographs together?

Big Appetites was shot over the better part of a decade. Around the time I began I had only just switched to digital cameras and they were a bit rudimentary. I upgraded over the years and as they improved so did my work. The lighting was the hardest thing for me to work out with food photography. I think moving to Seattle in 2004 was a step forward in that the Pacific Northwest has flat, overcast skies for much of the year. It is really a perfect light for food photography and I prefer to shoot only with natural light. I had a large body of work by the time the photographs gained notoriety. When discussions began last year, with my excellent publisher Workman, they expressed interest in seeing new work in addition to the back catalogue. So I put my head down and worked very hard for many months. I was afraid there wouldn’t be enough they would like. However, I was relieved when they were so pleased with what I presented that they decided to make a longer book. Many people have seen my work as some of the images have been published – on websites and in newspapers and magazines – in around 100 countries. But I’m excited for people to see the large body of new work in the book for the first time.

What was your process for each one?

The process can vary. Sometimes I have an idea for which I’ll make sketches in advance. But most often I’ll choose foods opportunistically at the market. I’ll bring it back to my studio and I’ll work around the colour, texture and geometry of the food. After it is washed, cut and styled, I choose figures based on the context of how they’re interacting with the artichokes, or apples, etc. On certain days it works. At other times it doesn’t. I might strike the set and try another food. I’ll sometimes come back to things later. Once I’m satisfied with the composition then it is just a matter of adjusting lighting and running through different choices for depth-of-field to give me options on how much of the frame is in focus. When I think I have it I’ll move on to digital editing. Occasionally figures need to be repainted or reconfigured digitally. And I’ll always have lots of clean-up to do. I always say that I chose food as a subject because it offers beautiful colour and texture. The truth is that we usually see food from an arm’s length and when one starts to photograph it with macro lenses all of the imperfections and flaws are revealed.

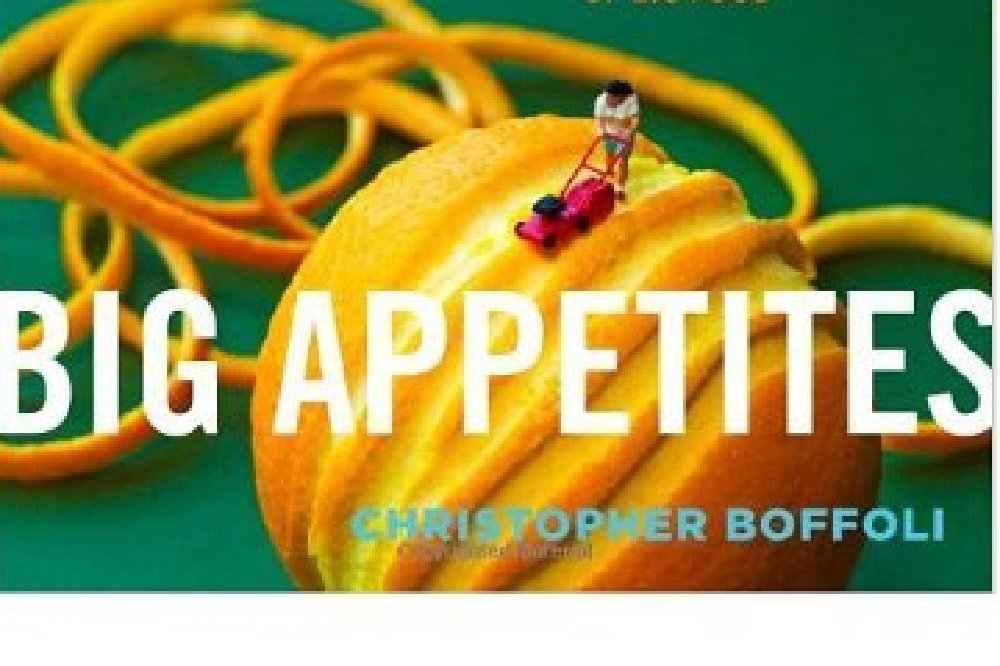

I’ve found that one of the most important aspects of this work is to be open to happy accidents. For example, the photo used for the cover of the book – Zesty Mower – was made on a day when I wasn’t even shooting. I was carving a long strip of orange rind when it occurred to me that the gauge of the channel I was making would fit a tiny lawnmower that I had. So I set it up and shot it in about 15 minutes. That image went on to be featured on the show card for my first solo exhibition and it looks as though it will be the first photograph in my catalogue to sell out of edition. Sometimes I labour over an elaborate photo that no one seems to connect to later. But of course the one that was easiest to shoot ends up being the one everyone loves. I wish I could take credit for being clever but sometimes the truth defies a simple explanation. You can make photographs for decades and still not always know precisely what makes a successful image. Being able to respond to doors of creative opportunity as they open is key.

You are also a journalist, writer and filmmaker, so can you tell us a little about these areas of your life?

Again, in addition to working as a student journalist when I was younger, I studied English and Literature at University. But my career afterwards was in Educational Philanthropy. I worked on capital campaigns for elite schools like Dartmouth College and the London School of Economics, raising private money so that really smart young students could have access to top education. Though the work was not primarily creative, my skills as a writer, photographer and graphic designer certainly were welcome everywhere I worked. I did that for thirteen years and it was mostly stimulating and rewarding but I didn’t love it. A couple of life-changing experiences altered my course. I was a resident of lower Manhattan on September 11, 2001 and essentially watched thousands of people die from my apartment window. And then a few years later I was mountaineering at high elevation in the Cascade Mountains here in Washington State when I had a severe accident and narrowly escaped death. After I recovered I decided to take a creative sabbatical. I had already dabbled in film work so I continued to develop a few projects while also traveling quite a lot. I began to get photographs published in some travel magazines and eventually began writing feature stories as well. In a bit of lucky timing, a “hyper-local” news agency sprang up in my part of Seattle and its readership burgeoned at a time when newspapers were devolving. I covered features stories and spot news for them and had a blast exploring the adrenaline-filled world of breaking news at the same time I felt as though I was serving my community. Then Big Appetites began to get some traction and it was off to the races.

What is your favourite photograph from the collection?

You know, I’m constantly being asked that question and I honestly have to say that I find it much more interesting to know which ones other people like best. If you consider that many artists design their work to please themselves, the whole notion of articulating a preference for any of my own work feels slightly uncomfortable. By far one of the best aspects of the notoriety of these photographs is hearing from people who are engaging with and enjoying the work. It is very affirming to go to exhibitions and hearing people laughing at my captions, seeing them appreciating the visuals, and asking questions. That’s always fun for me.

But with all of that said, being completely candid, if pressed I’d say I tend to prefer some of the images that are darker in tone (which you won’t find in the book). It goes back to the inspiration of the Travellers series. I thought that work was brilliant, especially because it presented rather dark little scenes. I love the notion of luring in a viewer with a snow globe – something that is usually whimsical and light-hearted – and then turning on the fulcrum of their expectations to present something unexpected.

What’s next for you?

That’s a surprisingly American question. I’m not often asked that by European journalists. In America it is never enough to do one good thing. There must always be something else. The appetite is never sated by one doughnut. We have to sell them by the dozen.

My immediate plans are to survive the autumn. In addition to doing press to support the book, I have three fine art shows in three countries in the month of October (UK, Canada and the US). And I’m negotiating a possible exhibition in Hong Kong at year’s end and also working on a number of commercial commission offers, one of which would need to be shot in Sydney. I’m already putting some exhibitions on the calendar for 2014. And I’m extremely fortunate that orders for fine art photographs are rolling in steadily. I do still have a list of ideas and sketches for some more Big Appetites photographs. But I’ve also been developing designs for an entirely new body of work which will move away from scale figures but that will still involve food. So I’m looking forward to clearing my plate, so to speak, and embarking on new work after the holidays.

Big Appetites: Tiny People in a World of Big Food by Christopher Boffoli (Workman, £8.99). Copyright 2013. Photographs by Christopher Boffoli.