Few have the privileges I was brought up with: a famous father, a nanny, public school, travel, a childhood spent in different countries. It’s certainly true, though, that wealth and position may bring material comfort but not always emotional contentment and fulfilment. We have all heard about how difficult it is to emerge from the shadow of an important and dominant father figure, and they don’t come much more important that mine: Lieutenant General Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, 1st Baron Norrie, GCMG, GCVO, CB, DSO, MC & Bar. Leading a cavalry charge in September 1914, he captured the first German guns of the Great War. As a Corps Commander during the North African Campaign 1941-1942, he found himself pitched against the intrepid German general Erwin Rommel. On retirement from the army, he became Governor of South Australia and later became the eighth Governor-General of New Zealand.

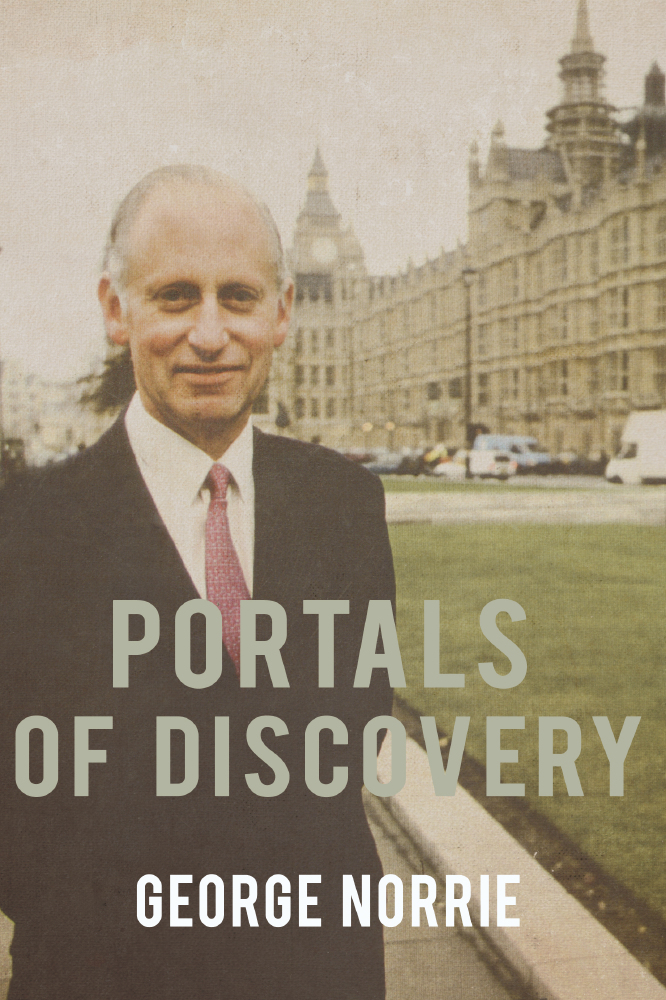

George Norrie

My father was larger than life and loved by many, including myself, but our relationship would seem strange to many today. Public service and boarding school meant prolonged separation of parents from children and the difficulties of sea travel – this was long before routine transcontinental flights- made things worse. It might seem shocking to many, for instance, that when in 1936 my sister died tragically young at school in England, neither my mother nor father were able to travel home from India until many months afterwards. It was a different time, with different conditions and different expectations. As children we were expected to cope with the vagaries life cast up with that famous stiff upper lip, and I had my nanny, a seminal figure, but nonetheless separation and tragedies took a toll that perhaps I was only to recognise much later in life.

As the son of a soldier I was expected to follow in my father’s footsteps into the army, which I did- for a while. My book ‘Portals of Discovery, is derived from a quote by James Joyce: “A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.” Never in any sense have I considered myself a genius, but I do believe that by living through your mistakes you may, if you’re fortunate, arrive at self-knowledge. I hope I have found my way through that doorway, at least to an extent. One important legacy my father left was his hereditary title, which came with a seat in the House of Lords. I discovered I had a zeal for environmental causes and played, I hope, no small part in legislation designed to establish and protect the National Parks of England and Wales. My leaving of the House when the legislative changes came in 1999 left a hole in my life but led nevertheless to this book, which is a reassessment of my life and relationships. I would recommend it to the reader for two reasons: first I think it is of interest as a historical narrative, giving insights to my and my father’s life and times: secondly I would like to hope it would serve as an inspiration to others who may at one time or another have felt sidelined or subsumed. It is possible, I hope I show, to find your own path, be your own person and finally reach a kind of contentment.

Portals of Discovery is available from The Book Guild