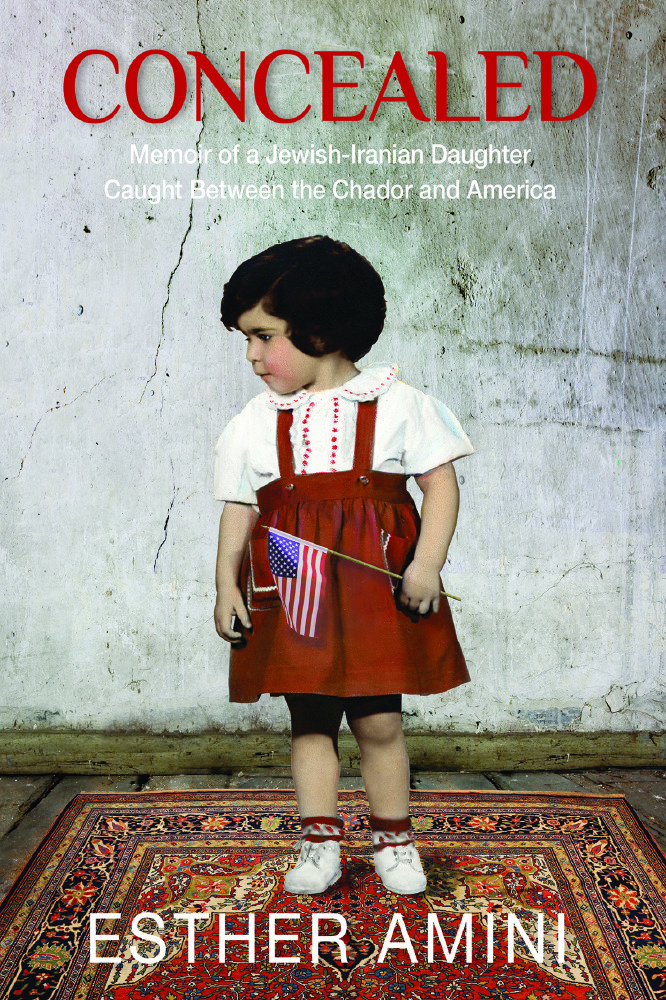

Courage: I recently wrote a memoir entitled: “Concealed” about growing up first generation American in my Persian home. My parents were Orthodox Jews from the Iranian city of Mashhad. Orphaned at birth, my mother was strong-armed at age fourteen into marrying my then thirty-four-year-old father. Mashhad is the most intolerant and most fanatically Islamic city in all of Iran. Here, of all places, they lived underground lives, like the Marranos of Spain. Due to life-threatening anti-Semitism, my mother wore the black chador and my father prayed from the Koran in public squares, each posing as Muslim. However, within the privacy of their home they were devout Jews. At the end of World War II, incensed by persecution, Mom dragooned Pop and my two brothers to the States. Later, in America, I was born.

Concealed - Memoir Ester Amini

Telling my story required courage—much more than I ever knew was needed. Cultural taboos psychologically surfaced; thoughts such as: The Mashhadi Jews are today still an underground community and highly secretive. They don’t write about themselves, at least not in this transparent way. Dare I defy Persian prohibitions? Dare I share what is private?

From the first syllable to the very last page of “Concealed,” written words felt like smuggled imports. You mustn’t tell, and if you do, you’ll be found hanging from a tree. This was my nonstop inner refrain.

Digging: Reaching in, excavating early childhood memories requires muscle. “Dig deeper,” my highly attuned editor would say. “There is so much more to uncover.” And to my amazement, she was absolutely correct. With shovel in hand, I unearthed parts of my past I had conveniently repressed. One recollection lead to another, as storage rooms of memory swung wide open. My father’s suicidal hunger strike when I chose to move into Barnard College, was only one. Back then, he believed an educated daughter was a curse, since she’d eventually become a whore, a wanton woman, selling her services on the street. Another forgotten echo from the past was of my swashbuckling, illiterate mother, entering places that forbade entry—such as Oscar de la Renta’s private showroom, with me placed firmly by her side. Some reminiscences were side-splittingly funny, while others weren’t quite so.

The Unexpected: I thought telling my story of growing up with Persian parents tethered to Iran during America’s free-wheeling 1960’s, with bras burning and the feminist movement burgeoning, would be primarily about the humorous and painful cultural clashes. It wasn’t! Penning my life led me down roads I hadn’t traveled before and offered startling insights. I learned if I let the story take the lead, it will end up in a far more truthful place.

Consolidation: Describing childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and later myself as a mother became an integrative experience. That certainly wasn’t why I thought I was writing. I believed I had a special story that needed to be told, especially since all of my female ancestors from both my patrilineal and matrilineal lines couldn’t read or write. Being the first educated female in my family, I felt an obligation to tell their story and mine. Yet, much more happened. I came to know me in ways I hadn’t before. As a result of writing this book, my contradictory, self-opposing sides began to consolidate into one unified whole. I had not expected this to be the result.

Pining for Iran: While born and bred in New York City, I grew up in an Iranian home releasing gobs of feelings, jingling tambourines, saffron rice steaming, the scent of home-made stews lacing through our hallways, Iranian marzipan, as well as Persian love songs crooning from turntables. From birth I was addressed and sung to in Farsi, an ancient tongue offering a peek into the land of my parents. How odd to be shaped by a culture I’ll never be allowed to see. A homeland buried within me and out of reach. Iran is a phantom mother twisting her eyes, whispering do’s and don’t’s, shadowing me daily. I can feel her hot breath, hear her high-pitched voice, but it’s the face-to-face we haven’t had, and very likely won’t. For that, I pine. If today, as a Jewish-American female with a Persian last name, I dared to step foot on Iranian soil, I’d be viewed as a threat, accused of entering the country as a spy, and held captive with no recourse---not even a U.S. Embassy to turn to. As a result of writing “Concealed,” I feel this loss.

Catch-22: In the midst of writing, I was surprised to see how members of my family were afraid they were in my memoir, while concurrently feeling spurned if they weren’t. “Concealed” isn’t about defaming family, disclosing infidelities, or in any way engaged in character assassination. I was not prepared for this unexpected conundrum.

Rounds of Editing: If I had been told right from the start it was going to take 5 years to write “Concealed,” I would have balked. I knew I had a story that had never been told and I was ready to write and deliver it within a year. Yet, I discovered it isn’t about the first or second draft, but rather the rounds and rounds of editing that became the actual work. And to my surprise, I thoroughly enjoyed writing and rewriting…no matter how many years it took. With each new version I experienced an adrenalin rush, and found myself engaged, engrossed and in love with the process.

Book in Hand: Once “Concealed” was printed, I received a hard copy in the mail for review. I stared at the cover, held the book against my chest and wept. Anyone who writes a memoir must confront their internal shusher, urging them not to reveal. My silencer was different. In the world my father came from, books were kept far from females, with the conviction: the less girls knew, the better wives they became. He often reminded me that his mother, at the tender age of 9 married his 29-year-old father, and later he at the age of 34 married my 14-year-old mother. “Women don’t need books.” And though he meant well, here I was holding mine. A miraculous experience.

Readers: A memoir is a time-defying preservation of self. Its moral function is to say the uncomfortable, the unsavory truth of one’s being, with hopes that readers will also feel less alone. To my great delight, men and women of all ages, races, and religions have reached out telling me how much they’ve enjoyed “Concealed” and how my specific story speaks to them, even though their cultures and traditions are different. What I never knew, was that a memoir can also make the author feel less alone.

Esther Amini EstherAmini.com Author of: “Concealed”—Memoir of a Jewish-Iranian Daughter Caught Between, the Chador and America