A basic search online for “Strong Female Characters” will throw up a front page populated by articles explaining why it’s time the term was retired, and I wholeheartedly agree. It looks as though we’ve finally realised that Strong Female Character has come to mean Girl Who Embodies The Masculine Ideal Of Strength. Which is not what strength is at all.

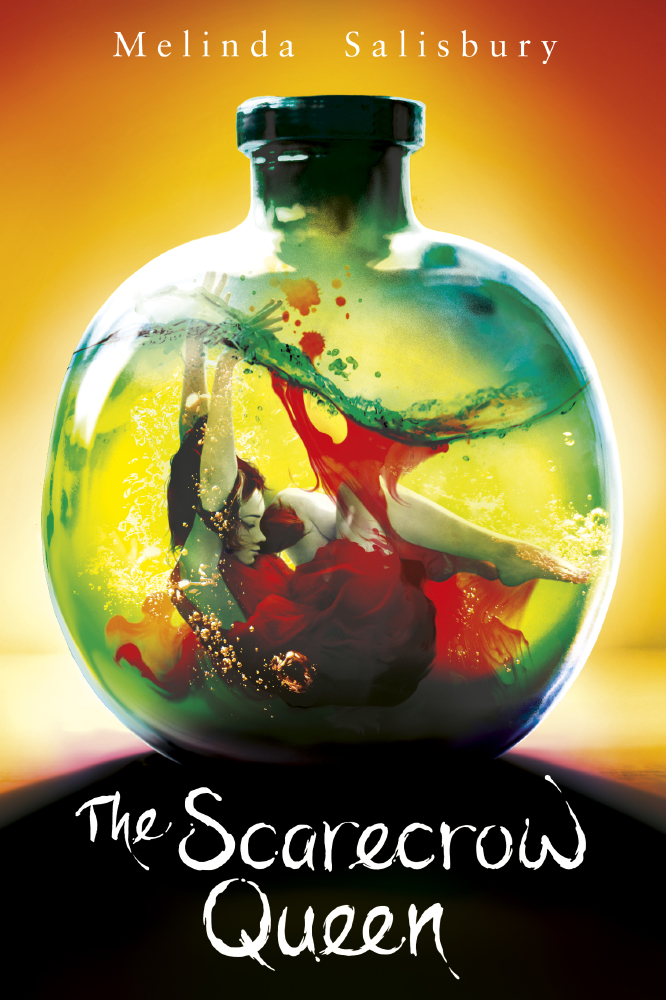

The Scarecrow Queen

For a while there, a female character would only be considered strong if she matched up to certain criteria – she had to be good in a fight, reluctant to lose her heart, quick with the perfect scathing retort, a confirmed Lone Wolf. If she was ruthless, she was strong. If she was physically fit, and also impossibly beautiful, she was somehow strong. If she shut her feelings in a box, she could be called strong. The ability to kill, or injure, without remorse or guilt made her very strong – she did what had to be done and she didn’t cause a fuss, didn’t let pesky emotions get in the way of her goals. In short, in order to be considered strong, a young woman had to behave in the manner defined by that ultimate benchmark of admirability – the masculine lens.

Though this depiction of women is a few degrees better than the Damsel in Distress of days gone by, in isolation this newer definition of strength still does a disservice to both women, and men, because it reinforces a very black and white picture of what strength - and therefore weakness - is.

Thankfully, the tide is turning though, both on page and off. Fictional heroines like Sansa Stark, Wing Jones, Paige Mahoney, Eleanor Douglas and Nina Zenik are proving there are different ways for girls – for people - to be strong; through perseverance, self-belief, determination, trust, and teamwork. And in the real world, we’ve seen Michelle Obama, Hilary Clinton, and Gina Miller standing on the front lines of highly charged political situations, deflecting criticism and attacks with poise, grace, and determination. We’ve seen Malala Yousafzai, and Emma Watson, talk passionately and eloquently about education, and feminism, all without shouting, swearing, or using violence, verbal or physical. We’ve seen Beyoncé, gloriously and unashamedly pregnant, commanding a stage and celebrating three generations of the women in her family. We have real role models who fight with compassion and understanding, who stand with their allies and seek out new ones, who are open and who empathise – and who are undeniably strong.

The current definition for Strong Female Characters is as two dimensional and offensive as the Damsel In Distress trope, and I’m thrilled we’re moving towards a time when female - and male - characters are allowed to be fully diverse in their characteristics, and for that to mean not dividing them up into arbitrary strong/weak boxes. After all, so much is being done to break down gender barriers in the real world, from letting toys be toys, to the ever-growing conversations about feminism and how it benefits everyone, that it seems almost embarrassing to expect fictional heroes and heroines to stick to some archaic ideas about what strength is.

So what does it mean to be strong? For me, it’s having integrity of self. It’s asking for what you deserve, being willing to work for it, and refusing to accept less than that. It’s knowing which battles to fight, and when it’s the right thing to back down, and save it for another day. It’s standing beside other people, standing up for those who are weaker than you, or less privileged than you. Being strong is always trying to be your best self, and to be kind, and generous, and understanding, even when the world around you is making that hard. It’s keeping an open mind, and an open heart.

When not working on her next novel Melinda Salisbury is busy reading and travelling, both of which are now more addictions than hobbies. She lives by the sea, somewhere in the south of England.

The Scarecrow Queen is the highly anticipated and captivating finale in the internationally bestselling trilogy that began with The Sin Eater’s Daughter. Published by Scholastic 2 March 2017.