What are you most afraid of?

The most convincing ghost stories are the ones that come from a genuine place of fear in the author. What scares you – is it the good old-fashioned misty figure glimpsed in a remote location (O, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad); is it the creepy children who know more than they should (The Turn of the Screw); is it the haunted house (The Woman in Black); is it the ghost of a child (The Little Stranger); or is it something more earthly – the psychology of isolation and the threat of madness (Dark Matter)? If your subject unsettles you, it shows.

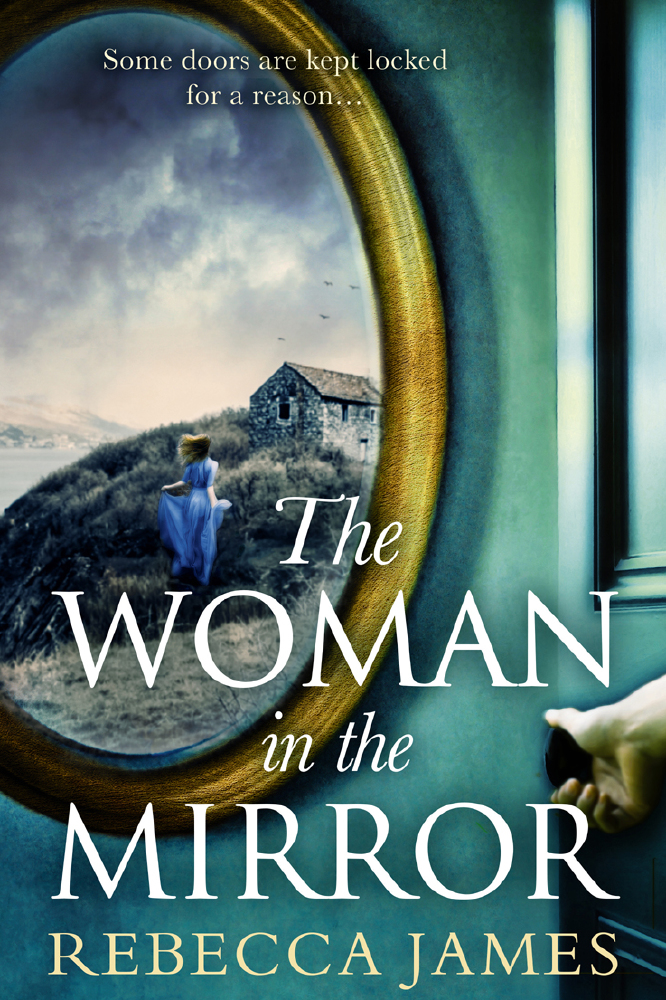

Rebecca James

You’re part of a tradition

Quite unlike any other genre, the ghost story draws heavily on its ancestors, reappears in different forms for different generations, and, in that sense, is something of a ghost itself. Don’t be afraid to borrow heritage you admire and twist it into a terror all your own. This is the way with fear: think of those urban legends we swopped at school, the dog under the bed or the couple in the car; they all overlapped with each other, recycled endlessly by teenagers across the land, and to some extent it didn’t matter whether they were true or not, the joy was in the retelling. I have long loved the classic Victorian ghost story – authors like M R James, Elizabeth Gaskell and Henry James: I just think they really knew what they were doing – and I wanted to pay homage to those greats with The Woman in the Mirror. I think readers like to stumble on to ground they recognise in a ghost story, whether it’s a slamming door, a glimpsed shadow in a window, or a windswept location pierced by ravens’ cries – it’s all part of the fun.

Choose your stage set

That’s how I think about ghost stories, as being set on a stage rather than in a landscape. Imagine the spooky lighting, the smoke that comes up from the orchestra pit, the clash of cymbals when something drastic happens. In The Woman in the Mirror I definitely wanted a big dilapidated country pile, but I also wanted to situate it in the wild rugged moors of Cornwall. On a writers’ retreat in Cornwall years ago, we were hemmed in for days in a thick sea mist. Surroundings were unrecognisable, shapes amorphous, distances confusing: it was really eerie. I thought if I could capture some of that disorientation and isolation in my book then my stage set was doing its job.

Less is more

How many times have you seen a horror movie, been scared witless by the dark and the shadows, then as soon as the monster is revealed, you think: Oh, that’s it? Bear this in mind when you’re writing your ghost story. Help the reader to draw their own monsters because whatever they conjure in their imagination will be a fright tailored to them, and far worse than anything you can prescribe. A fine example of this is The Blair Witch Project. At the start, the filmmakers sketch out an image of the witch by giving us a handful of details about her appearance. This is just enough to find her outline – but the rest is up to us. And, as anyone who saw that film when it first came out knows, the result was terrifying.

Leave it hanging

...and not just your helpless prey. All the best ghost stories have a sting in the tail: the reader reaches the end, ready to breathe a sigh of relief but with the tantalising anticipation that the story might not be done with them yet – and then, on the last page, it reaches out and gives them a pinch. Because that’s the ultimate ghost, isn’t it – that thing that comes back to grab you just when you least expect it.