Susan Cooper Bridgewater

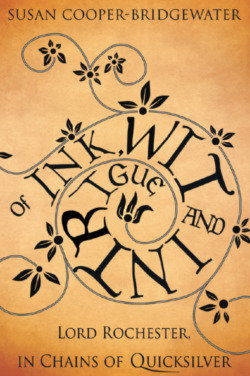

Of Ink, Wit and Intrigue, Lord Rochester, in Chains of Quicksilver is my first published novel. It’s a curious historical fiction, allegedly penned by the hand of the true-life, infamous John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, one of England’s most notorious wastrels, wits, poets and libertines at Charles II’s Court. He vividly narrates the intimate events of his odd and audacious life in England and abroad. I have created a book with an unusual, quirky edge, in that it invites the reader to journey in the company of the charismatic Rochester as he candidly recounts his inimitable life, from birth to death. The story however does not end with his demise, but continues with an intriguing epilogue.

Why is the restoration period in our history so appealing to you?

The period, I feel, is one of the most important times in England’s history in bringing the long awaited restoration of the monarchy, following the years of Cromwell’s oppressive regime. The welcome return of Charles II, known for his love of science, the arts and female company, brought expectations of a more liberated culture. The elaborate attire for those who could afford it, in the wearing of rich silks, satins and lace and the fashion for men of wearing a peruke, emulating that worn by their voguish King, all added colour once again to their enforced drab lives under Cromwell. Women of the day enjoyed the freedom of a liberal use of make-up, false hair pieces and dresses in the finest of materials, especially fashioned to reveal their feminine charms. And for some of their number, there was a rightful place to act in public upon the London stage. In this wondrous liberated age, citizens could once again enjoy the playhouses, street fairs, Christmas celebrations and the delightful pleasure gardens such as the famous Vauxhall. For the more serious minded of the age, The Royal Society was founded and granted a Charter by the newly restored King which enabled the great mathematicians, astronomers and other scientists of the day a free hand to study, experiment in and lecture upon their specialist subjects without fear of reprisals. But, as a realistic historian, I do not view those times through rose tinted spectacles and know only too well that beneath that glamorous Carolean façade there were the realities of abject poverty, the daily hazard of disease in all quarters of the streets and homes and never ending political unrest.

Please tell us a bit about John Wilmot.

John Wilmot was born on the 1st of April 1647 at Ditchley in Oxfordshire. He was the son of Henry Wilmot, 1st Earl of Rochester and Anne his wife. Both parents had been widowed from their first marriages. John knew little of his father, who sadly died abroad in exile in 1658 when the boy was just 11 years old and inherited the title of the 2nd Earl. John was educated at Burford Grammar School and later at Wadham College in Oxford. On gaining his MA, at the age of 14, he left England for the Grand Tour in the company of Dr Andrew Balfour. On his return in 1664 he was welcomed at the Court of Charles II. A tall elegant handsome fellow with an astonishingly sharp, clever wit, he was very soon the darling of the Court, beloved equally by males and females alike. His fondness for strong drink contributed greatly to his natural charismatic charm but he soon found himself drawn irreversibly into the company of the less salubrious courtiers.

Rochester’s choice of a bride, one Elizabeth Malet, a wealthy heiress of Somerset and a match much encouraged by the King himself was not easily secured, she having many affluent suitors vying for her attention. Young, in love, impulsive and reckless, John took it upon himself to abduct the beauty of the west, but the attempt failed miserably and ended, for him, with a spell of incarceration in the Tower of London for his pains. Eventually released from those confines, he proved his worth as a brave gentleman volunteer under the command of the Earl of Sandwich during the skirmishes with the Dutch fleet and returned to the Court looked upon as a hero.

All this impressed the young heiress so much that in 1667 they dared to elope and were secretly married, much to the astonishment of both their families. The union took place at Knightsbridge Chapel in London, known for clandestine marriages.

His married life was a turbulent one. At times he shared peaceful family domesticity with his wife and children, whilst at others his life was one of a wayward courtier with all the pleasures that offered in carnal gratification. Predominately, he was torn between wife and mistress, his Maîtresse-en-titre being the actress Mrs. Elizabeth Barry.

This young, virile, handsome courtier of exceptional intelligence found himself in an uncontrollable downward spiral past the point of no return. Ill health, through overindulgence in the pleasures of Baccus and of Venus, was to be this Earl’s ruin, but sadly time ran out for dear Rochester and on the 26th of July 1680, in his 33rd year, he breathed his last.

Why did he fascinate you so much?

As an historical researcher, you are spoilt for choice with so many fascinating characters in the Restoration period but for me Lord Rochester stands out from the crowd. His natural charisma, bolstered by his witty poetical writings of both shocking lewdness, and of breath-taking passionate love and his endearing letters all of which reveal so much of his gritty and humorous outlook on life, drew me to him. Rochester’s character is mystifying and one which many a scholar has tried to fathom. Although at times you think you know him well, at others he challenges your perceptions. He continues to fascinate me.

Please tell us about your research process into the book.

I have for many years held a passionate curiosity for England’s colourful history, with particular emphasis on the Restoration period and its people, and in 2006 I began my research into the life of Lord Rochester. Apart from the usual study of specific documentation relevant to him, I also researched many aspects of those times by reading numerous excellent academic and non-fiction works of the period. I was also most fortunate indeed in that I live relatively near to the idyllic Cotswolds of Rochester’s birth and it was by travelling in the footsteps of the man, I was able to capture the historic reality of his life there. And the icing on the cake for me was that through my own determined in-depth research, I viewed, in the flesh so to speak, the bed (sadly it was in a grave dilapidated state) that was the famous scene of the repentant Rochester’s poignant demise.

What made you want to tell it from Rochester’s point of view?

Scripting the story in the first person came naturally to me from page one. I felt it was crucial to relate his story from that angle so as to breathe life and spirit once more into this fascinating historic character.

What is next for you?

I am currently working on an historical novel telling the stories of my ancestors, the Bridgewaters. My own genealogical research of them has turned up some remarkable individuals. I also have plans to write my first non-fiction biography of a 17th century female figure whose life I am in the throes of researching.