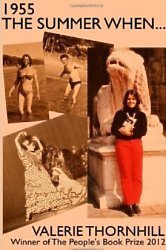

Valerie Thornhill at the book launch

Some years ago when our children were young, we bought a ruin in Italy. Friends with young children joined us and we spent our holidays reading, walking, visiting interesting places, swimming – and recounting stories. I seemed to have done a lot of this, telling the children about various adventures on my travels.

‘Write them down! Write a book!’ they clamoured. So I did. Some are used in my first novel In Restoration, and others have appeared separately. I always knew that the summer of 1955 changed my life, and that what occurred had a natural coherence. A lot of other things have happened to me, but they are too widely spaced to make sense except in an autobiography, and that will never be written.

Why was it so unusual at the time for a young woman to travel alone?

Women were supposed to travel with their families or at least with a female friend as had been usual in the pre-war years. Particularly after the war, there was the fear of unwanted pregnancies and that young women could be led astray. This was before the pill, and after the many unwanted war children, often fathered by soldiers who then left. (That is an issue which affects Olivia in my previous novel, In Restoration, Winner of The People’s Book Prize, 2012). Also, female attractiveness was then associated with vulnerability, the need to be protected and so on. That attitude didn’t suit me at all.

What prompted you to go travelling in the first place?

After ‘O’ levels I went to Guildford Technical College to become a secretary and earn money quickly. However a brilliant teacher picked me out of a class studying French and encouraged me to do ‘A’ levels and even the entrance examinations for Oxford and Cambridge Universities. Obviously, I had to study French, as that was his subject and he was doing all he could to help me. Though I was better in English and Maths than languages, I loved writing and literature, so applied to study languages at Cambridge. I had been abroad once before, while at school, to stay with a family in France on an exchange programme. When I was invited to stay with my professor in Paris, I jumped at the chance!

What was your most memorable adventure on your travels?

That’s really difficult. So many were memorable. Perhaps the most magical was the banquet at the palazzo in Genoa, but the most frightening was the attempt, in the Alhambra, Granada, to abduct me, ship me off to S. America on a raft of false promises and into the ‘white slave trade’

Where was your favourite place from the trip?

Venice. I was with young people from all over Europe, free while the money lasted to enjoy each other’s company in this enchanted city before it succumbed to mass tourism. It was also there that I began to feel at first hand the tragic effect that the war had on young people like Miklos from Yugoslavia.

How did people react to your independence and headstrong nature in a time when it was not really the norm?

Surprise. The American couple in the train to Paris, right at the start of my journey, wondered how my parents could allow me to travel alone when still under the age of consent. In Andalucía the fact that I managed to travel on my own led the Señora to trust me to chaperone her daughter, though I was only nineteen and Carmen was all of 25! The more unscrupulous, such as Signor Palumbo plying his dubious trade in Genoa, thought I was there for the taking. The young people in Hamburg, many of them war orphans, welcomed me to help them in their task of rebuilding lives shattered by my country’s bombing to end the conflict.

What was Europe like in the 50s compared to now?

I am highly irritated by people who assume that the Fifties were ‘grey’. Though there were still bomb sites all over European cities, there was a new energy, a new start, a will to pull together to get everything going. There was a lot of sharing and helping. People talked more at doors and along the street. There were many clubs and chances to socialise without spending a lot, as most had little disposable income then. Only the wealthier middle classes had black and white television. We used to listen to radio a lot, to the young people’s serial stories, and then phone our friends to discuss them. We had a lot of outside hobbies. I rode ponies and saved up on newspaper rounds to buy my own – but that’s another story!

There was no mass tourism. Bliss, in retrospect. We could climb up St. Mark’s in Venice and go out on the balcony to overlook the square while touching the bronze horses, probably removed from Constantinople in the 13th century. Now there are copies and the originals are displayed inside and out of touch. It’s the same for the Parthenon and Stonehenge, to mention only two great monuments that one now has to admire from afar. We were there. We could feel close to them and the artists who created them. It was still a very small world. I bumped into my university friend in Milan and people who knew my landlady in Seville. Would this be likely nowadays?

Advertising was far less intrusive. Without the factual overkill of the internet, there was far more to discover in Europe.

So no mobiles, just the fixed line, and phone calls from abroad were expensive. Postcards and letters were the way we kept in touch with our parents and friends. People had to be patient. I also think there was less fear about what might happen to me without TV. Today images on our screens from everywhere seem to make us more fearful than similar events then only described on the radio. Now such events are felt to be inside the home rather than happening elsewhere.

In spite of the pill and of instant means of satellite and internet, people seem more fearful now. Then there were fewer communications, less news, and so parents and friends didn’t worry for no reason and were glad of the postcard and, if lucky, a letter. Then I must have been closer to my ancestors in the 18th and 19th centuries who wrote treasured letters on thin paper covering both sides, then turning them round and writing another page hopping over the words on the original upright one. One page instead of two cost less. A month or six weeks later these precious letters would arrive.

We travelled by train as the age of the commercial plane was only just beginning. Encounters on trains feature in many a novel, while speed and less friendly seating patterns, have less dramatic potential, witness my journey from Seville to Ronda (Chap. 11). Everything happened more slowly, so there was more time and space for people to talk, read and think.

What is next for you?

Before writing 1955 The Summer When... I finished the first draft of the most ambitious novel I will probably ever write. I’ve started to revise it and write about the task in my blog creatinganovel.wordpress.com I hope it will become a discussion platform for both readers and writers. My current novel is totally different from anything I have ever written, and the more challenging for that. I know that the following book will draw on my ancestors in the Indian Raj. That’s as much as I’m planning for now!