On a mild Spring day in the village of Hagley in Worcestershire, four young boys were scouring the woods for birds’ nests when they came upon a large wych elm tree. It’s safe to say, as they dug into the hollow of the trunk, that the last things they expected to find were the grisly remains of a woman.

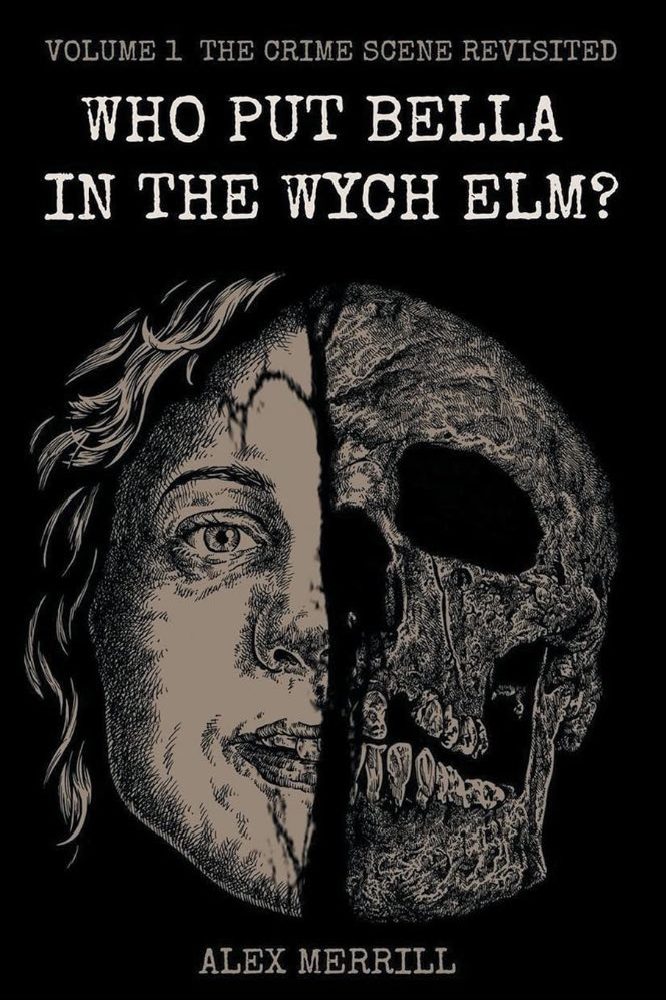

The skull of "Bella" / Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

When Robert Hart, Thomas Willetts, Bob Farmer and Fred Payne came upon a human skull in a wych elm of Hagley Wood (on the sprawling estate belonging to Lord Cobham) on Sunday, April 18th 1943, they first decided to keep the discovery to themselves, out of fear of being reprimanded for trespassing. But the youngest boy, Thomas, soon found that he would not sleep until he had told his parents what he had witnessed, and there began one of the most mysterious murder cases in English history.

The police arrived on the scene and, after getting a lumberjack in to tear down the tree, found a near complete skeleton, alongside a shoe, a cheap gold wedding band and some pieces of clothing. The skull still had hair attached, as well as most of its teeth.

“There were no limbs and no parts of limbs,” said forensic biologist John Lund on BBC Radio 4’s Punt PI in 2014. “What was left was what the animals hadn’t torn up.”

Under forensic examination, it was found that the skeleton was that of an approximately 35-year-old female, 5 ft in height with light brown hair, who must have died in or before October 1941. Her front incisors were slightly overlapping, and there was a chunk of taffeta in her mouth, giving a possible cause of death as suffocation.

It became clear as the tree was being torn down that she must have been stuffed into the tree either alive or very shortly after death, before rigor mortis had occurred. What’s more, it would’ve proven a very difficult task for just one person.

Lund deduced that the clothing was mostly “poor quality” and that he couldn’t find any trace of a dress or a skirt as one might expect, until Webster told him of the cloth stuffed in the skull. “It turned out to be the skirt,” he said.

Despite a decent collection of evidence, police were unable to match their findings with any reports of missing persons in the region, nor could they find any dental records to match the distinctive dental pattern of the skull.

And so the mystery remained baffling and unsolved, with no further evidence arriving until 1944, when a strange bit of graffiti was found on a wall in Birmingham nearly 12 miles away as the crow flies: “Who put Bella down the Wych Elm – Hagley Wood.” More graffiti appeared in a similar hand around the town, all asking a similar sentiment. Later, a message reading: “Who put Bella in the Witch Elm?” appeared on the Wychbury Obelisk.

Even as forensic technology advanced, police were unable to uncover more evidence as the bones mysteriously disappeared from the university which housed them. Stranger still, all records regarding the body are now unaccounted for.

There were stories linking the murder to witchcraft, with whispers of covens meeting in and around Wychbury Hill, and the remains of a hand also found in the vicinity of the other remains has led many to suspect occult involvement.

Contemporary Pagan authority Ronald Hutton revealed that while a detached hand doesn’t hold occult significance in itself, there is a tradition regarding the ‘Hand of Glory’, which is usually a hand cut from an executed criminal and used in magic. This was a theory presented initially by folklorist Margaret Murray, but Hutton remains unconvinced of it in this case because there were no strange objects on or around the body to suggest a ritual killing, nor was there anything significant with regards to the position of the body (save for it being jammed into a tree).

Other sources suggest that Bella may have been an enemy spy in WW2, though there is no firm evidence to support this claim either. However, there was a letter written to the local newspaper, Express & Star, by one “Anna from Claverley” who claimed that the victim was Dutch and the murderer was also now dead.

“One person who could give the answer is now beyond the jurisdiction of earthly courts,” she wrote. “Much as I hate having to use a nom de plume, I think you would appreciate it if you knew me. The only clues I can give you are that the person responsible for the crime died insane in 1942 and the victim was Dutch and arrived illegally in England about 1941.”

One woman who claimed to be a relative later identified Anna as Una Mossop; the wife of a man named Jack Mossop who worked in ammunitions in the war and was something of a suspicious character. He’d apparently been seen in an RAF uniform even though he wasn’t in the RAF, hung around with a Dutchman and even confessed to passing on information to the Germans to his wife. His death certificate revealed that he died aged just 29 at a mental hospital in Stafford.

In 1953, Una Mossop sent a statement to the police: “March or April 1941… Said he had been to the Lyttelton Arms with Van Ralt and the ‘Dutch piece’ and she had got awkward. She had passed out. They went to a wood and stuck her in a hollow tree. Van Ralt said she would come to her senses the following morning.”

Una mentioned that Jack had had recurring nightmares about the woman in the tree, which ultimately led to his incarceration and death at the Stafford mental hospital. Van Ralt, meanwhile, was never found. While this statement is most telling at first glance, it may not be the most reliable of sources when you consider it took her twelve years to take her story to the police.

More theories surrounding possible espionage came with the story of German spy and the last man to be executed at the Tower of London, Josef Jakobs. Upon his arrest in 1941, a photo of his cabaret singer girlfriend Clara Bauerle was found on him and he revealed that she was being trained up as a spy. However, Bauerle was thought to be 6 ft which is at odds with the victim’s 5 ft approximation, and in 2016 it was discovered that she had died in Berlin in 1942.

Perhaps a more likely story (as theorised by Punt PI) is that Bella was merely some poor woman who’d been at the mercy of a rapist and murderer. Another statement dated April 7th 1944 revealed that a German sex worker told a detective that a woman named Bella who used to frequent Hagley Road had been missing for about three years.

Indeed, the poor quality clothes John Lund had spoken about would certainly fit this theory, as well as the crooked teeth and lack of dental records which speak of someone who was particularly hard-up. Her skirt having been taken off and stuffed in her mouth could suggest a rape took place. And while it might appear that the presence of a wedding ring negates the idea that the victim was a sex worker, it wasn’t uncommon for unmarried women to wear wedding rings to avoid social scrutiny in those days.

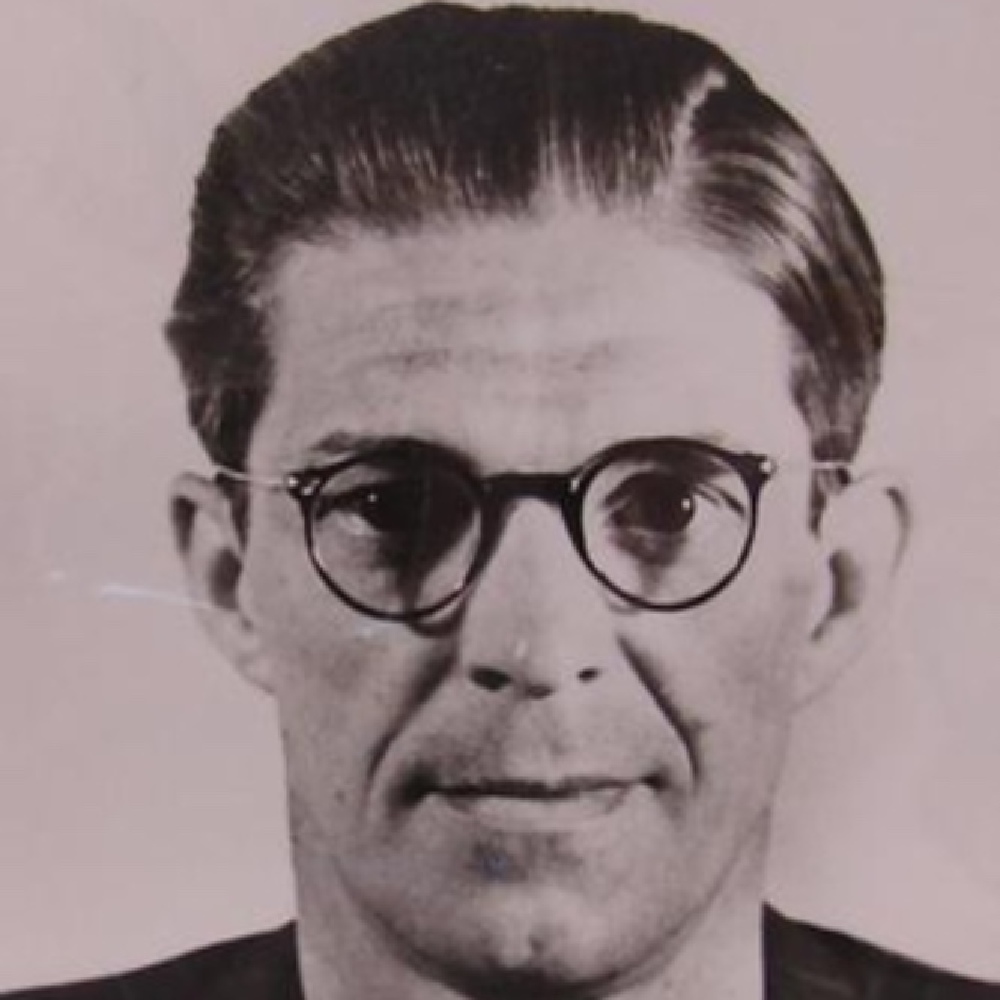

We’ll probably never know who Bella was, or if Bella was even the name of the victim, but we may have an idea of what she looked like. A reconstruction of her face was undertaken at the Liverpool John Moores University's "Face Lab" using photographs of the skull, and images were revealed in the book Who Put Bella In The Wych Elm?: Volume 1: The Crime Scene Revisited by Alex and Pete Merrill.

MORE: Who killed Charles Walton? Witchcraft or workaday, we examine The Pitchfork Murder

One thing’s for sure; someone must have known the area well enough to hide the body, or otherwise been incredibly lucky to come across the hollow wych elm in the depths of Hagley Wood, which will now forever be haunted by our unknown victim.

Tagged in Murder